Diāna Tamane is known in Latvia as a conceptual photographer who explores her family ties and private archives, revealing intertwining ideologies, regimes, beliefs and experiences. In Half-Love, the artist continues to develop this interest, focusing this time on her half-sister Elīna, who is not only the central character of the exhibition, but also their kinship explains the “half” in the exhibition’s title.

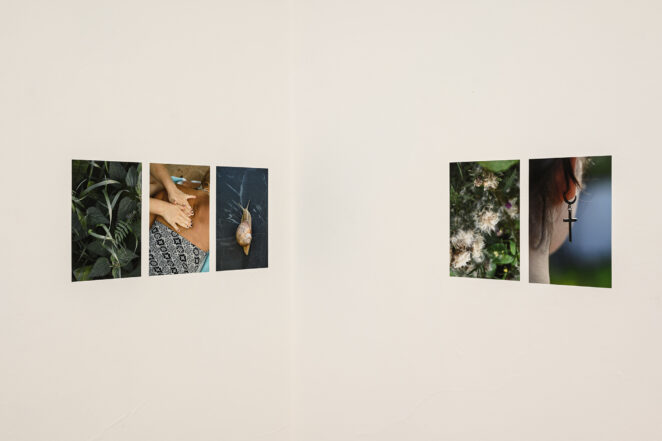

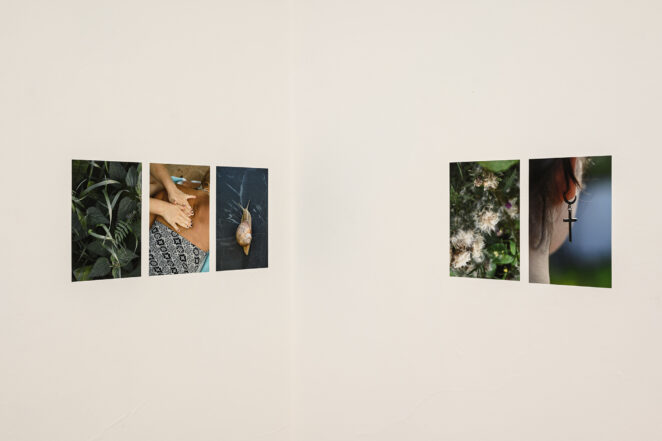

View from Riga Photography Biennial – NEXT 2023 Diāna Tamane’s solo exhibition “Half-Love”. Photo: Ingus Bajārs

Upon entering the exhibition, however, one immediately notices the difference between this series and her others – here the images are bathed in a warm light reminiscent of the rays of a setting sun.

View from Riga Photography Biennial – NEXT 2023 Diāna Tamane’s solo exhibition “Half-Love”. Photo: Ingus Bajārs

The overall atmosphere of the works also seems to be chosen to match the season: in early summer the motifs of childhood memories, summer cottages, the sea, verdant and fertile gardens warm many hearts.

In the photographs displayed on the museum’s lower level, we see portraits of Elīna taken in the same place – the greenhouse – across several years. The changes that we see in the greenhouse’s interior allow for the possibility that it is being rebuilt.

View from Riga Photography Biennial – NEXT 2023 Diāna Tamane’s solo exhibition “Half-Love”. Photo: Ingus Bajārs

With the scenery constantly changing, we see processes rather than identities in the photographs. In the early pictures, an intricate cluster of blooming weeds ensconces the girl, while, in later images, pumpkins, lettuce and the most popular greenhouse plant – the tomato – replace the mugwort and lesser celandine.

Colorful ribbons hold them upright, creating a rhythmic vertical pattern. The way in which the images are arranged conjures a sense of linear motion that also reflects the girl’s growing up – except for her serious, questioning gaze, Elīna is different in every picture.

Most of the photos have been taken using a classic approach, capturing the girl’s face and upper body from the front, as well as her changing outfits and accessories. Elīna doesn’t smile in the photographs but rather the corners of her lips tend to droop.

The greenhouse setting invokes themes of care, nurture and warmth that resonate with horticultural principles, as well as being echoed in social theories about the possibilities of constructing, or more precisely, reconstructing society. In this framework, we can think of sisterly love as a protective environment – a microclimate in which not only people, but also certain feelings, beliefs and forms of relationships can grow and flourish.

Diāna’s letter to Elīna – a companion to the exhibition – reinforces this interpretation. In the letter, the older sister encourages her younger sibling to be independent and self-sufficient, while remaining perceptive and considerate towards others – both human and non-human beings.

Plants also appear further on in the exhibition on the top floor of the museum, where the photographs are arranged more loosely, in non-linear clusters in which any new element may cause an unpredictable, surprising effect. This part of the exhibition enables getting better acquainted with the cottage setting, the courtyard and the garden, and invites going beyond its borders, letting the sand from the beach fill your shoes.

View from Riga Photography Biennial – NEXT 2023 Diāna Tamane’s solo exhibition “Half-Love”. Photo: Ingus Bajārs

However, one cannot shake the feeling that Diāna Tamane is observing the scene from the position of an outsider – transformed into perfect still lifes, the cottage interior expresses a distance that alienates her from the flow of daily life and domestic bustle, so that these moments would be easier to remember later on.

Although the presence of the plants in the photographs can be read as a testimony to the passage of time and, at the same time, as a metaphor for sisters growing up together, there is also another take that emphasizes the active presence of plants in the interaction between the two sisters.

The museum’s upstairs hall displays different-sized photographs of plant leaves, flowers, fruits or seeds, interspersed with portraits of Elīna, close-ups of her body parts and affective narratives of everyday life. A snail crawls slowly into the compositions of people and flora, or a random butterfly, which I cannot classify, flits over them.

In the letter to her sister, Diāna quotes the Zen Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, who teaches us to walk “as if you are kissing the Earth with your feet”. Diāna also takes a picture of her sister’s feet – covered in goosebumps and scratches, possibly mosquito-bitten and with a small scar on the left knee cap.

In classic Western philosophy plants rank the lowest in the hierarchy of living beings – compared to humans and animals, they were considered more primitive and less evolved, mute, passive and inert. The influence of this belief is still felt today. For example, in how “passively vegetative” is considered one of the saddest states a person can find themselves in.

However, not all human beings have had an equal chance to experience this superiority in relation to plants: Western philosophy has mainly attributed this privilege to the white male who alone, according to many thinkers, possesses rationality – the trait that sets people apart from other beings.

In this sense, women, children, “savages” and animals had never fully freed themselves from nature’s embrace, or struggled greatly to do so (like the Suffragettes of the late 19th century). The connection to nature, which is often contrasted with culture, was used as a means to justify oppressing and controlling certain social groups in the name of a civilization based on rationalism.

It is true that today the idea of naturalness is being revisited. The best-known examples of its rehabilitation can be found in the “green farming” and “green living” movements, which have intensified in the face of the pandemic, and in recreation – we like to spend our time off close to nature.

Nature is once again being conceived as a temple where people, overwhelmed by civilization, can reclaim their “self”. Whereas the philosophical interrogation of the relationship between plants and people seeks to register new constellations of knowledge, materiality and power. These impulses are driving, for example, the field of plant humanities in its search for unconventional answers to Western philosophy’s classic questions about subjectivity, identity and culture.

This very brief glimpse into the intertwining of plant, posthuman and feminist theories allows us to see both the critical potential and the intriguing beauty of Half-Love. The plants in the photographs aren’t simply backgrounds, decorations or resources, but one agent in a complex web of relationships involving not only the artist’s extended family, who live in a holiday village once shaped by Soviet policy, but also contemporary social and economic agents, such as the market economy.

In one of the clusters of photographs, we see six images of a clearcut. In each picture a lone pine tree that resembles a gravestone – the laws governing deforestation require individual trees to be left to grow – sinks deeper into a thicket of freshly regrown shrubs.

I can’t say how many years it would take to restore the relationships destroyed by clearcutting, or whether this is entirely possible. The solitary tree becomes a peculiar connection point, closing the gap between two distinct temporalities – the anthropocentric human activities driven by economic considerations, and the cyclicity and complexity of forest life.

Not only do the six photographs that document the forest’s regrowth materialize the passage of time, but also illustrate the forest’s own agency to heal or soften the damage done, licking the ax wounds with their green tongues.

In one photo we see that Elīna too has plasters on both knees, and we can recall the previously seen image of the scar on her knee cap. Feet that kiss the ground sometimes bleed. It is not only stones that wear them down but also human indifference, greed or lust for power.

Both the tree and the human body are vulnerable – the practices of repair and maintainance were put forward by feminist theory, including art, as early as the 1960s as an alternative to the neoliberal, profit- and progress-oriented Western society, while the knowledge of the healing powers of plants is held by many traditional cultures, including the Latvian.

It is easy to idealize or misunderstand plant-human relationships, or to view them through the lens of their benefit to people. Interactions with plants are often far more political than they may first appear. However, the French philosopher Luce Irigaray draws our attention to the hospitality and generosity that also characterize the vegetal world.

These characteristics are manifested in the way that the plants create an environment where we can survive. By providing humans with oxygen, plants create an “aero placenta” that not only sustains life but also, as Irigaray writes, faith in life.

Hospitality and generosity also figure in Diāna Tamane’s photographic gaze as she addresses her younger sister, figuratively sending her oxygen. The connection between the two sisters extends beyond a blood relationship, forming a more-than-human family tree whose branches bend under the weight of the pumpkin/Earth.

Diāna Tamane’s photographs also give continuity to the second wave feminist idea of sisterhood as an empowering political strategy. This is seen in the call to “think without the head”, as philosopher Michael Marder describes plant-thinking, or to think with your feet, as Thich Nhat Hanh might say.

It is precisely the “primitive” status of plants that opens up new possibilities for Western culture and allows us to interrogate the autonomous and rational self in order to bring out our vitality, creativity and responsibility towards the environment and other beings, including by noticing the hitherto unappreciated parallels between philosophical, art and vegetation processes.

Summers are short, and the time sisters can spend together is even shorter – much less than half a lifetime. Yet these moments are part of infinity, like grains of sand on a sister’s back or stars on a summer night.

Diāna Tamane’s solo exhibition ‘Half-Love’ at the Latvian Museum of Photography was on view till July 23.

The review was originally posted on arterritory.com”

View from Riga Photography Biennial – NEXT 2023 Diāna Tamane’s solo exhibition “Half-Love”. Photo: Ingus Bajārs: