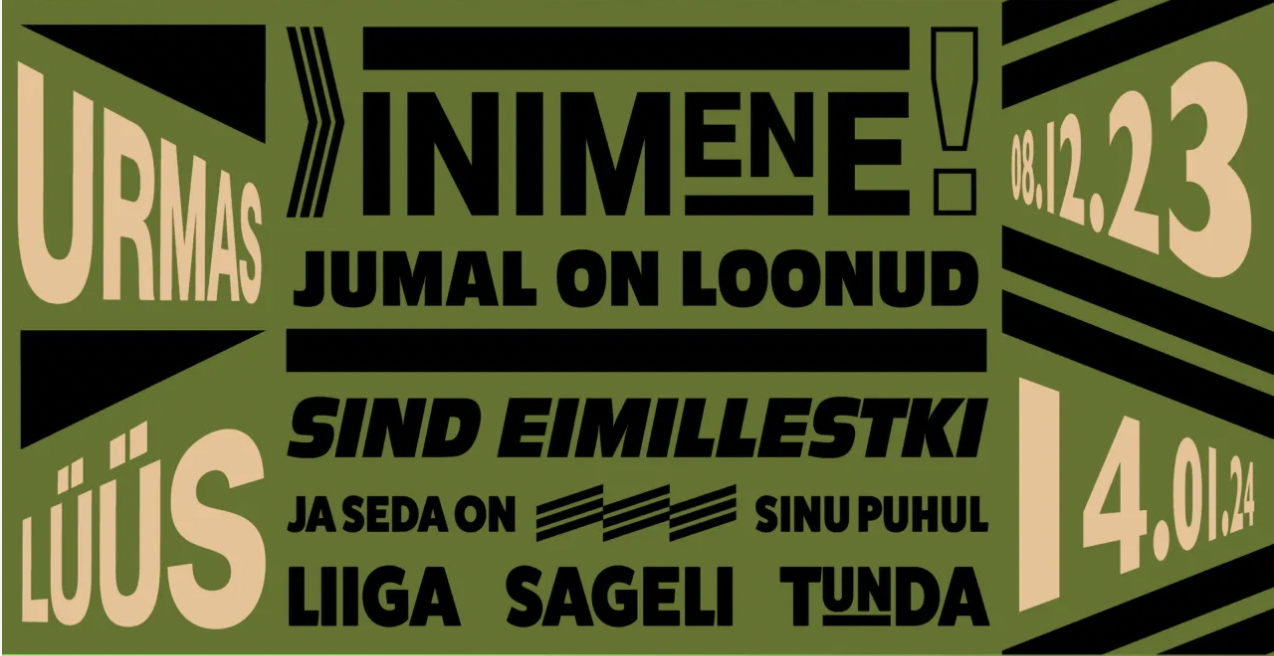

Urmas Lüüs’ solo exhibition “Man! God Has Created You Out of Nothing, and This is Too Often Felt in Your Case” will open at Tütar Gallery in Tallinn. Having once again produced a large-scale, almost total installation in the vein of Kabakov, bearing a title borrowed from Arvo Valton and recreating the atmosphere inspired by the Catholic cemeteries seen in French villages, Lüüs poses a question that appears again and again in classical art, which has assumed new relevance in our time: “How do you ask the dust?” (John Fante)

Urmas Lüüs is known for his expressive contemporary art, in which various creative identities intersect and overlap. A blacksmith by trade, he has dabbled in performing arts, jewellery, noise music and installations, and taught and written about art. I have a feeling that Lüüs, as an artist, or more broadly as a creator, has always taken delight in situations where he comes off as a bit of an outsider, as though eyeing someone else’s backyard.

Art critics and curators have often associated Urmas Lüüs’ work with neo-materialism. This trend is reflected in the belief that an artistic text is sustained primarily by embodied labour, by the energy inherent in the personal, poetic manipulation of material. Realisation, therefore, is anything but secondary, because thinking itself proceeds through manual search. As such, neo-materialist art seems to irk the neo-platonic idea-centric imagination typical of mainstream post-conceptualism, whereby it makes no difference whether an artist realises their project themselves or hires diligent craftsmen from a remote Chinese manufactory. At the broadest level, however, it implies a conscious rejection of the dominant operating models of both the industrial production society and the service-based information society, without becoming obsessed with nostalgia and craftsmanship. Lüüs uses traditional techniques, from embroidery to blacksmithing, but often in unusual, skewed contexts, so as to open up unique registers of manual thinking.

It’s more than refreshing to see contemporary art offer the opportunity to take the Bible off the shelf and trace the lines of Ecclesiastes to deliver a sermon: “Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless, a chasing after the wind.” Humour aside, the jauntily pessimistic effect of Lüüs’ new installation is an escape route from the ever more insistent demand to choose sides everywhere and to take to the barricades to make ourselves heard. This conviction, which increasingly oppresses contemporary cultural consciousness through intensifying political crises and which is accompanied by the further exacerbation of the “crisis of subtlety” (Hasso Krull), can in fact only be relativised in the impermeable private space of poetry, without imposing a clear moral on anyone. To paraphrase the artist himself: “plurality is acceptable because evil does not invalidate bad and bad does not negate good.”

As Lutheran heirs to the ‘Danse Macabre’, it is easy for us to embrace the thoroughly democratic message of Notke’s painting, declaring all men equal before death—kings and beggars alike. In the world of kitsch Catholic votive offerings that has fascinated Lüüs in this case, things seem more complicated. The smaller works displayed in the installation appear to be characterised by sacramentality – the invisible and spiritual is present through the visible and material, which in turn is made sacred by its presence. In view of this, it seems fair to ask: who dares to claim that “no man brings souvenirs from beyond the grave”? (Gennadi S. Klein)

I would like to conclude with Anders Härm’s words about Lüüs’ (and Hans-Otto Ojaste’s) previous exhibition: “In a total installation, you must surrender yourself completely, leaving you no choice but to see the exhibition yourself.” Which was, of course, the point all along.

Accompanying text: Hanno Soans

Design: Juss Heinsalu

Graphic Design: Cristopher Siniväli

Technical Solution: Hans-Otto Ojaste

Installation Support: Erkki Kadarik

The exhibition is supported by the Cultural Endowment of Estonia, City of Tallinn and Koch Brewery

Galerii nimi: Tütar gallery

Address: Vesilennuki 24, 10415 Tallinn, Estonia

Opening hours: Wed-Fri 13:00 - 17:00 Sat-Sun 14:00 - 18:00

Open: 07.12.2023 — 14.01.2024

Types of art: Installation

Address: Vesilennuki 24, 10415 Tallinn, Estonia

Opening hours: Wed-Fri 13:00 - 17:00 Sat-Sun 14:00 - 18:00

Open: 07.12.2023 — 14.01.2024