I remember a story from a book about a person who got caught in a snowstorm on a vast field of ice and was led in the right direction by their gut feeling, an internal guide which might have been influenced by physics: the barely perceptible coldness of ice crystals on one cheek, the changes of light which the eye can scarcely sense. These are movements which can be registered only by the hypersensitive. This idea of a knowledge, that is first captured by the body and not by the world view of rational reasoning, might have been a belletristic exaggeration. But the cognition of the correct direction can arrive to us through the hairs on the back of our necks.

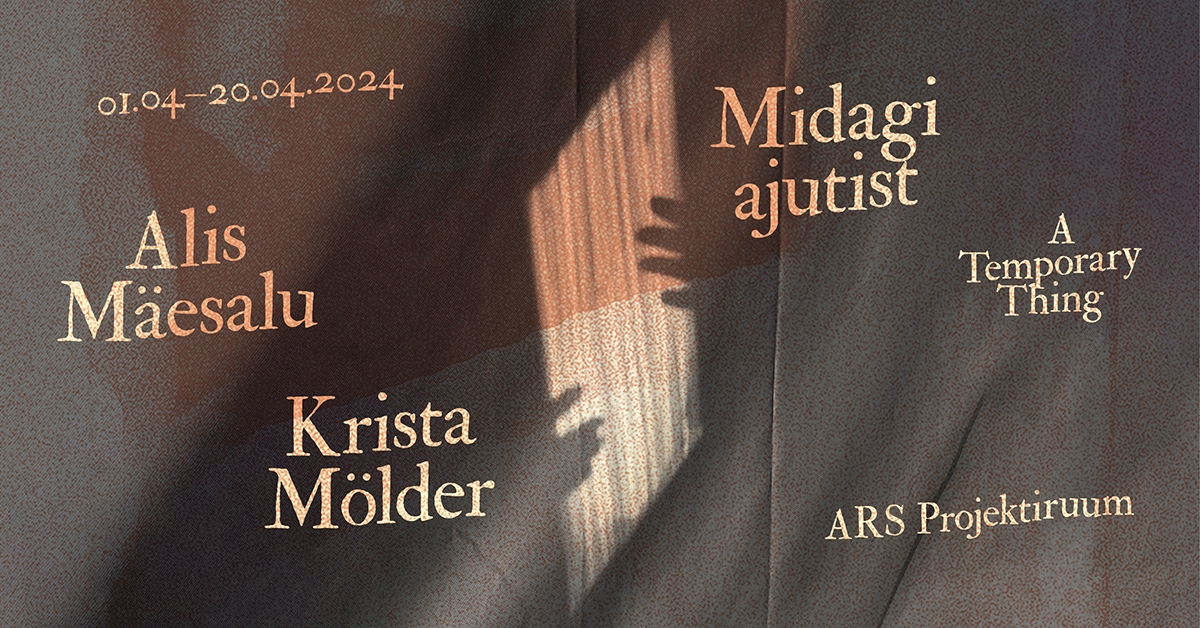

The works by Mölder and Mäesalu suggest an intermediacy, a transformation, trying to capture the moment between “not yet” and “already passed”. The time and the space reveal their amorphous visage. A thin plastic film might become the wing of a model airplane. A silver mirror which does not yet contain the photographic image or from where it might already have slipped away somewhere else, back into nothingness. A propeller which does not rotate and is stationary. Or does the space around it move instead? It takes a lot of patience, barely breathing, to create the ethereal.

When you forget yourself while you are observing something, your breathing becomes slower. The body freezes and becomes utter attention; the “me” is glued together with the thing observed, it fades into the surroundings, disappears. A new “me” emerges which is broader than the limits of one’s own skin, of one’s name, an assemblage which has inseparably been integrated into the world.

For the philosopher Gilbert Simondon, becoming the self – either as a person, a primrose or a clay brick – is not something isolated from the surrounding environment nor a process with a definite final outcome. The plant doesn’t germinate from the seed on its own, but has to tie together the energy from the sun with the minerals from the soil whereby its growth will also affect the balance of the latter. Simondon understood becoming the self, individuation, as an open and multilayered process which is based on the constant co-creation of each other and the environment through mutual relations. Becoming the self draws the power of transformation from the pre-individual phase where all the possibilities are open. The potentials contained within this phase will remain as latent components of the succeeding ones. (Vujanović, Cvejić 2022: 184–190) The tension arising in the exhibition of Mölder and Mäesalu feels like an invitation to change together, a certain latent potential whose trajectory cannot be anticipated. Something can enter a new state, can push something open; something that already exists in the space or in the viewer, something, which still has not made itself visible. Waiting for the perfect light, waiting for air.

Going swimming in the sea on an early foggy morning, bereft of wind and refreshing. Soon, the reference points disappear. There is only a narrow circle of waves around you and a dense, luminescent light engulfs everything. You are at the same time beset by an expansive feeling of freedom as well as the unease of confinement, euphoria as well as the fear of death. These do not cancel each other out or annul each other, instead undulating like the world around me. My head is spinning from the silence.

*Vujanović, Ana and Cvejić, Bojana 2022. Toward a Transindividual Self. Oslo: Oslo National Academy of Arts.

Indoor model plane F1D and inspiration: Ahto Sild

Experimental photography techniques: Jaanus Muruõis

Exhibition lighting: Revo Koplus

Exhibition text: Kerli Ever

Graphic design: Kersti Heile

Technical support: Karel Koplimets

Thanks: Maret Sarapu, Tiina Sarapu, Niina-Anneli Kaarnamo, Eve Margus, Indrek Mesi, Kristiina Hansen, Neeme Külm, Kristjan Pütsep, Kalle Pruuden, Märt Vaidla, Indrek Köster, Aksel Haagensen, Siim Soop, Peeter Talvistu, Marko Usler, Siim Vahur, Mari Volens, Villem Säre, Tarmo Rämmi, Craftrag, Holger Orek, SRIK vanamaterjal, Digifoto OÜ, KORDONair

The exhibition is supported by the Cultural Endowment of Estonia, Estonian Artists’ Associations, ARS, Temnikova & Kasela Gallery, Photography Department of the Estonian Academy of Arts