The exhibition and the second expanded edition of the book “Juhan Kuus, the Measure of Humanity” contains, in addition to his best works, 37 new photographs, most of which have not been publicly presented before. Most were selected from an earlier period of Juhan Kuus’s work, from 1970 to 1986. The photographs have been chosen from Juhan’s collection of negatives, which is now in the care of the Juhan Kuus Foundation.

Portrait Photography and Juhan

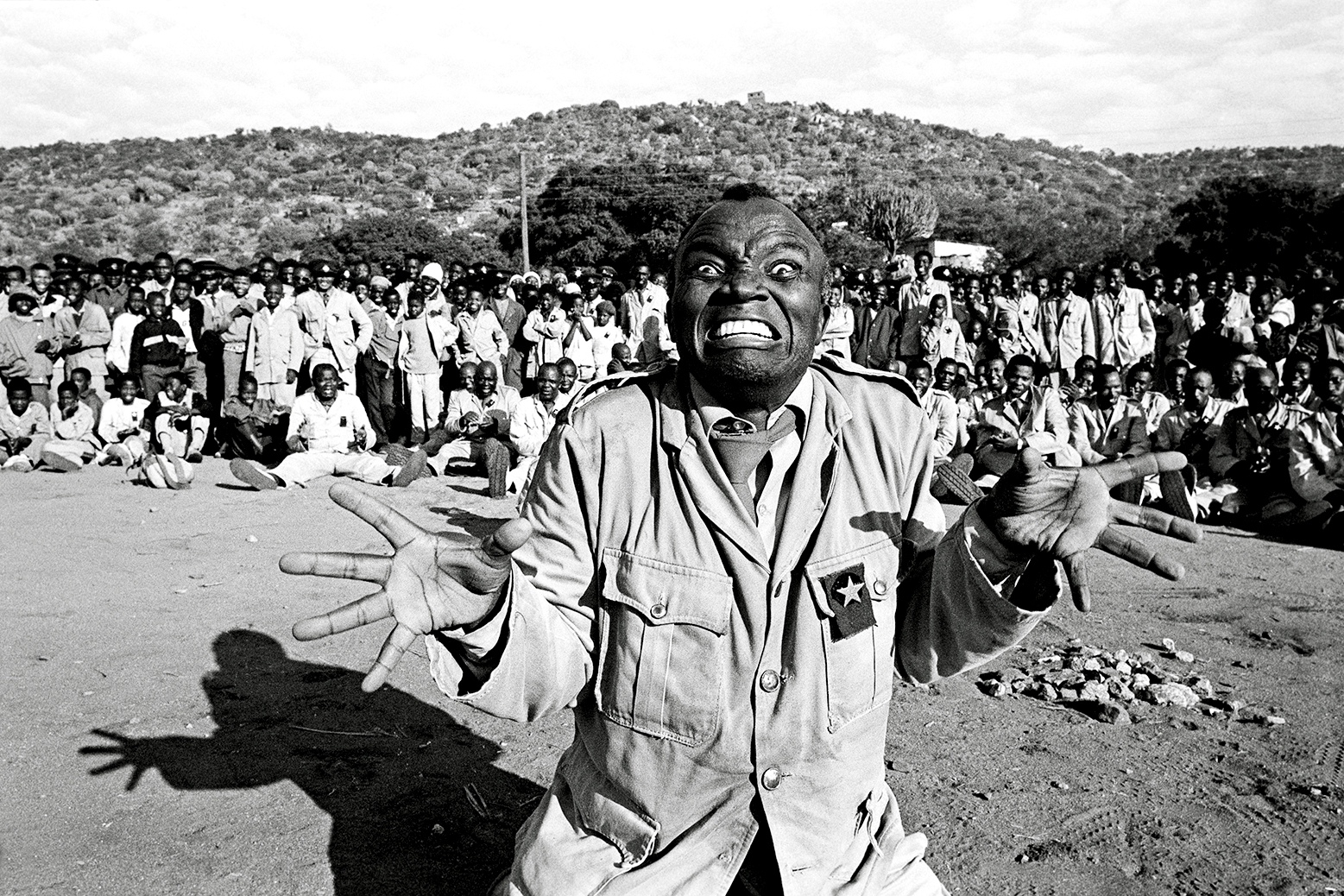

When Juhan photographed apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa, he always turned his camera on the people. He was never just fascinated by the environment of Homo sapiens but also by the people who faced him in this shared space and what they were doing or going through. Above all, he depicted the human environment in all its frailty, beauty and cruelty. His pictures are often a testimony to pain and suffering. Both in a literal sense, such as close-ups of young boys suffering at the hands of white apartheid soldiers, and in a more figurative sense, such as the poignant portraits of the homeless or the poor.

Juhan Kuus, who was self-taught in photography and had no higher education, was exceptionally well-read and had a broad knowledge of history, sociology, philosophy, and photography. Kuus was likely familiar with the work of the pioneers of social documentary photography, Jacob Riis, Lewis Hine and Dorothea Lange. His expressive portraits of marginalised individuals and people on the fringes of society can also be seen as socially conscious work. This is precisely what the three photographers mentioned above were doing as well. Sometimes, Juhan’s images also contain a casual or even deliberate element of irony and sarcasm, reflecting the contradictions of life and helping both the viewer and perhaps the photographer himself to deal with these complex issues and soften their effect.

Kuus was equally interested in the lives of black, mixed-race and white people. Thus, his oeuvre includes equally evocative portraits of apartheid ideologue Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd’s wife, Betsie Verwoerd, poor whites in Johannesburg, black minors in the Bosasa Horizon youth detention centre, the predominantly mixed-race population of the Bo-Kaap or Malay Quarter, or the rural farmers and their families of Oudtshoorn. In portraying the people of these neighbourhoods, Juhan sought to show the other side’s life — the invisible men and women who make the privileged white man in the more affluent neighbourhoods uneasy.

Juhan’s photographic legacy also includes some distinctive close-ups of South African political legends. Despite his long and extensive photographic work aimed at drawing attention to the segment of society that we should care more about, perhaps Juhan’s most internationally famous image is a double portrait of Nelson Mandela and Bill Clinton in prison on Robben Island. The story of the making of this photograph is also an essential story of Juhan’s unyielding character and dedication to his photographic purpose.

Interestingly, identifying criminals was one of the first practical uses of portrait photography. Although no one is known to have been directly prosecuted or punished based on the photographs Juhan took, his portrayal of the honest and ruthless violence of the apartheid regime has given rise to a debate about the collective condemnation of both the leaders and the perpetrators of the regime. The opportunity to see the scars of apartheid on society that Juhan captured is still relevant today – the parallels between world political events, local social problems and societal trends are not lost on us.