Samma’s work is known for queering seemingly harmless subject matter on national representation through explorations on sexuality and the notion of the public realm. Often, the concept of folklore is a re-occurring theme in Samma’s work as a form of cultural circulation open to queer re-interpretation. By using traditional techniques, the artist navigates through various forms of communication, which at first seem innocent but on closer inspection present an array of gay and queer symbolism. Through archival research, he has found ways of broadening the socio-political perspectives on national and sexual identity by offering alternatives for contextualising the past.

The exhibition at EKKM follows Samma’s recent curation at the Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design, in which he investigated the use of national patterns and motifs in Estonian applied art and printmaking between the 1930s and the 1950s. In this exhibition, Samma mainly explored how national iconography is connected to power and how it has shaped Estonians’ self-image.

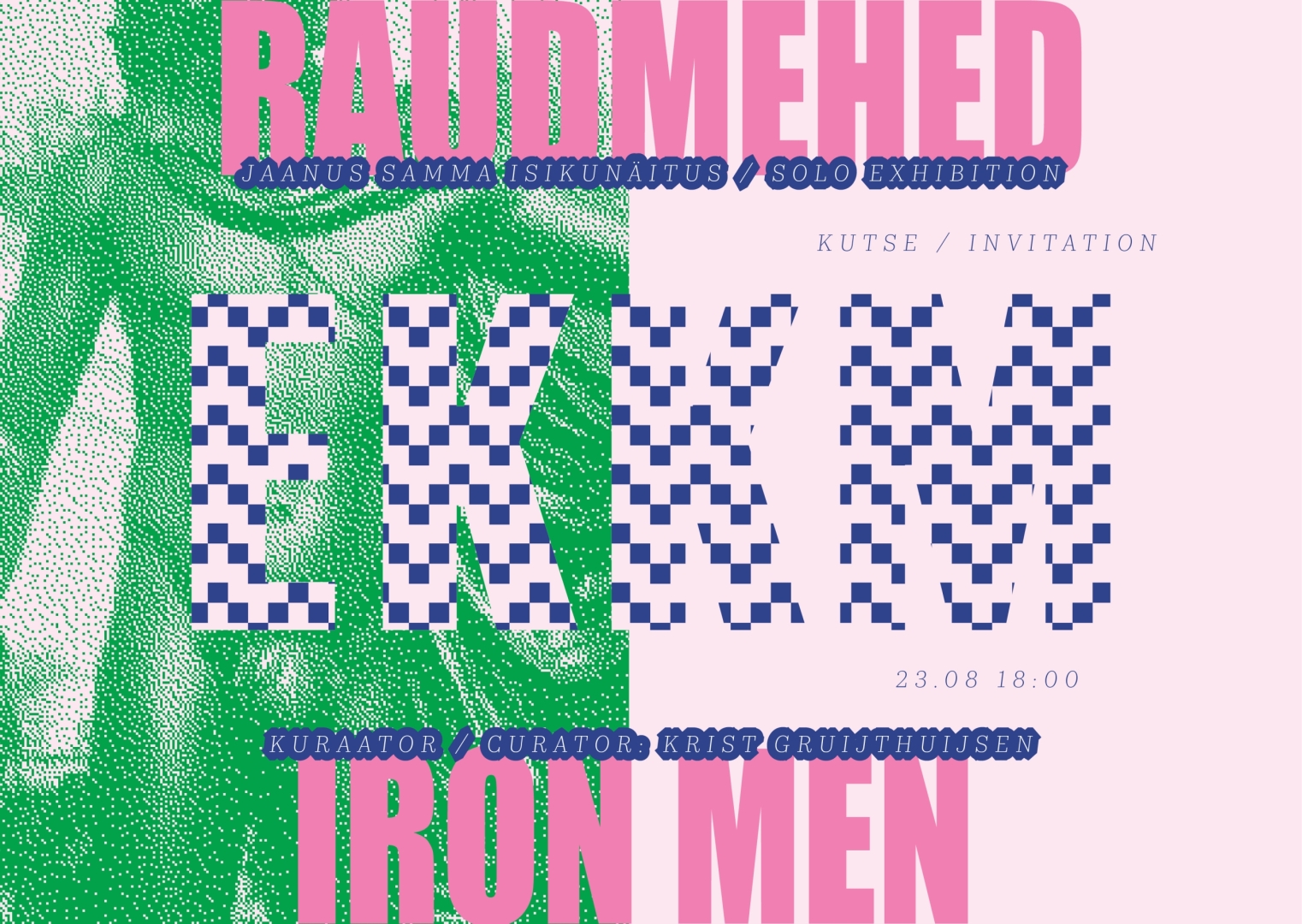

Iron Men focuses on a few elements that were included in that show, in particular the depiction of the so-called hero, one that symbolises and embodies strength, masculinity, protection and conviction, and he develops these further in artworks based on historical case studies. Without making a statement, the exhibition aims to connect several male protagonists who each have contributed to Estonia’s national pride, both in a mythological as well as political sense. Samma uses storytelling and forms of documentations to trace forgotten or overlooked histories in order to demasculinise the patriarchy.

The exhibition is divided into four sections. The first features a rug that the paramilitary youth organisation Home Daughters presented to Konstantin Päts, the first president of Estonia, in 1938 on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Republic of Estonia. The second section concentrates on Voldemar Päts’s publication entitled Estonian National Dress and Designs (1926), which had a significant influence on the output of many design studios and workshops in the 1920s and 1930s. Within the third section, the statue of Apollo takes centre stage, of which several copies appeared in Estonia in the years following the late 1880s. And finally, the last section queers the depiction of Kalevipoeg, a national symbol for the Estonian people.

With a light touch of irony, Iron Men playfully examines Estonia’s history and the men that are so proudly included in it.

At the exhibition, installations making an ironic comment of national myths, queering the image of the hero and eroding conservative morale.