Jüri Okas

Artist is based in: Estonia

Jüri Okas (b. 1950) began to actively pursue a career in art during the late sixties and early seventies, when young artists coming to the forefront introduced international, Anglo-American art trends, ideas and a different way of life. On the one hand, the artists met a well-established avantgarde canon, on the other hand, they lived in a closed society governed by totalitarian ideology and prescribed artistic ideals. The simultaneous co-existence of avantgarde ideas and a daily reality governed by an absurd desire to control history in the making, provided sufficient grounds for a irreconcilable conflict. However, this combination provided a wonderful opportunity for the artist to create his own personal vision and avantgarde con-ception. Jüri Okas presented an original synthesis, in which the anonymous architecture of North Estonia (often balancing on the absurd), and the deserted beaches of Vääna, were linked with minimalist and conceptualist notions.

Jüri Okas graduated from the Estonian Art University (former State Art Institute) in 1974 as an architect and is still active in the profession. The question always remains whether Okas studied architecture because he was obsessed with space, or whether he became obsessed with space while studying architecture. However, he has formed a very special relationship with space, regardless of his medium: print, film, installations or land art.

Jüri Okas is foremost an analyst and an observer. He does not meddle with objects and their relations, although selection and presentation themselves could be regarded as meddling. His subtle skill of observing and analysing is a point of departure for others – a clue – but nothing more. It is still a long way from perceiving the difference between recognizing and under-standing, between order and disorder. Perhaps the best examples of the artist’s ambivalency are his 8 mm films from 1970 – 1976, which totally lack any hierachy, either in form or con-tent; their only comment being the music of Frank Zappa.

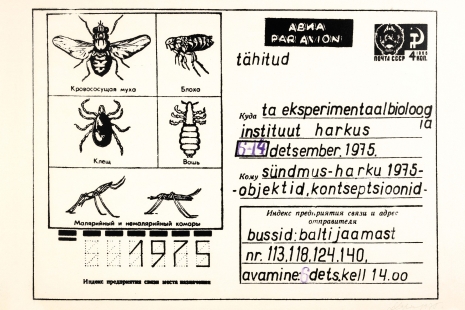

Immediately after his studies, Jüri Okas began presenting his works at exhibitions. He showed cityscapes in intaglio print where the usual informative message had been tampered with by the addition of signs and the transformation of space. The urban environment, already violated, was turned – by a further violation – into a spatial object devoid of any meaning. Then it was carried further into a picture, where the meaningless form was separated from its content by black rectangles, lines and arrows. Okas named them “Reconstructions” and as a matter of fact, they were large-scale installation views. Very soon his interest in the environment changed and took a turn towards the indirect and the abstract. By using stills and blow-ups from photographs and films, Okas elaborated the visual grammar of his art and system of rules, which is based upon the continuous exchange and substitution of the synthesis and analysis of meanings and signs.

In the early 1970s Jüri Okas explored a deserted beach at Vääna for creating his land art objects. The abstract character of the space made him mark it: for orienting, for grasping, for experimenting with his perception of reality. In these objects of sand, we perceive everything through opposites: through the wet shaped sand we perceive shapeless sand molded by the wind and the water, through the solidity and rigidity of man-made materials we perceive the sand structures easily falling apart, through the living and temporal human body we perceive the eternity of sand and sea. The installations, which were a natural continuation of land art objects, were shown at exhibitions. In them Jüri Okas studies further the various layers of meaning, adding to the peculiarities of materials the notion of an urbanised environment, with its ethics and conventions. In the largescale objects presented at the exhibitions under the common title of “Structure and Metaphysics” (1989-1990), he used asphalt, gravel and neon light, which signify a totally urbanised environment known and accepted by the artist. At his solo show in the Pori Art Museum (1991), he filled a large hall with bales of hay, but not from a romantic craving for nature. The closely pressed packages of hay, together with the broken pieces of asphalt and neon tubes, demonstrate a persistent wish to deal with the concept of order and disorder.

A Concise Dictionary of Modern Architecture, which was begun with the printing of his first photographs in 1974, can be seen as a kind of philosophical credo of Okas’ work. He has photographed more than 1000 buildings and sites in Estonia, including architectural objects with no particular style: odd, out of place and very often abandoned. The true builder of these objects is time, which has given leave to all temporary needs: windows have been boarded up, new doors have been cut through walls, dormers have been added, rooms have been walled-in; single fanciful turrets and trestles complement the host of oddities. Their irrationality is the outcome of a rationality too strictly followed.

Jüri Okas view is ironical, but not overtly so. Here too, Okas the analyst prevails, because in this manner he can question the basic principles of architecture. In the modern ambivalent context these questions are essential. What do we mean when we speak about deconstruction, ugliness, function, metaphysics, failure, style, etc.? The Dictionary is not a methodological study, without any philosophical concern. By exploring and seeking to understand the relationship of space and time in architecture, the artist (through these relations), deals with the concept of space which is abstract and hard to perceive. The oddity of buildings is one of human follies, for the artist the folly is in its relative projection onto the sensible orthodoxy.

Just as Jüri Okas follows his own aesthetics, the Dictionary follows certain ethical criteria. However, Okas is not a social critic; his handling of the subject is pervaded by a sense of the absurd and by independence.

While emphasizing Jüri Okas analytical approach, we cannot ignore his intuition and sensibility. Without these qualities it would be difficult to explore the ideas of rational – irrational, order – disorder, beauty – ugliness, continuation – disruption.

Text by Sirje Helme

Links to catalogues:

Jüri Okas 1995.a. raamat “Väike Moodsa Arhitektuuri Sõnastik”.

http://www.evaldokasemuuseum.ee/okas/j_okas/index.html

Jüri Okas Installatsioonid 1976-96

NIMETA. Jüri Okas. Fotod 1971-1993

Esimene Jüri Okase monograafia, ilmunud 2000. aastal.