The vigor of life is still the principal leitmotif of these paintings, be it expressed as reverence or remorse. The Greek word Pneuma denotes breath, spirit, and wind. As a term, it shares a conceptual world with the Hebrew ruacḥ רוח and the Latin spiritus, which, in turn, gave us the English spirit, via the Old French esprit. In any case, we are dealing with the spirit of life—our breath as energy, the wind enlivening the world. In Norwegian, we say “innånde” or “utånde” [to in-breathe/in-spirit, out-breathe/out-spirit], framed by the gestures of breathing in or out, as if the air was just as vital and indispensable for the continued existence of the soul as the body. This aspect was especially integral to Hippocratic medicine, and in Christian theology, Pneumatology signifies the particular study of the work and nature of the Holy Ghost.

Furthermore, from classical philosophy, Christianity inherited a crucial distinction between “soul” and “spirit.” Whereas the Greek Pneuma found its Vulgate translation in Spiritus, Anima was the Latin equivalent of the Greek Psykhē, a division mirroring the similar Hebrew bisection between ruacḥ and Nép̄eš/Nephesh נֶ֫פֶשׁ. Either way, the point remains the extent to which these terms surround, inform and define each other reciprocally, across disciplines. Similarly, Pneuma suggests something which is simultaneously absent and present—the wind breezing through these landscapes, the life-force that permeates, or rather perhaps permeated, the things of and in the world. Et in Arcadio Ego: a skeleton lies half-subsumed, half-visible in the partly flowering, partly decaying nature—death in life.

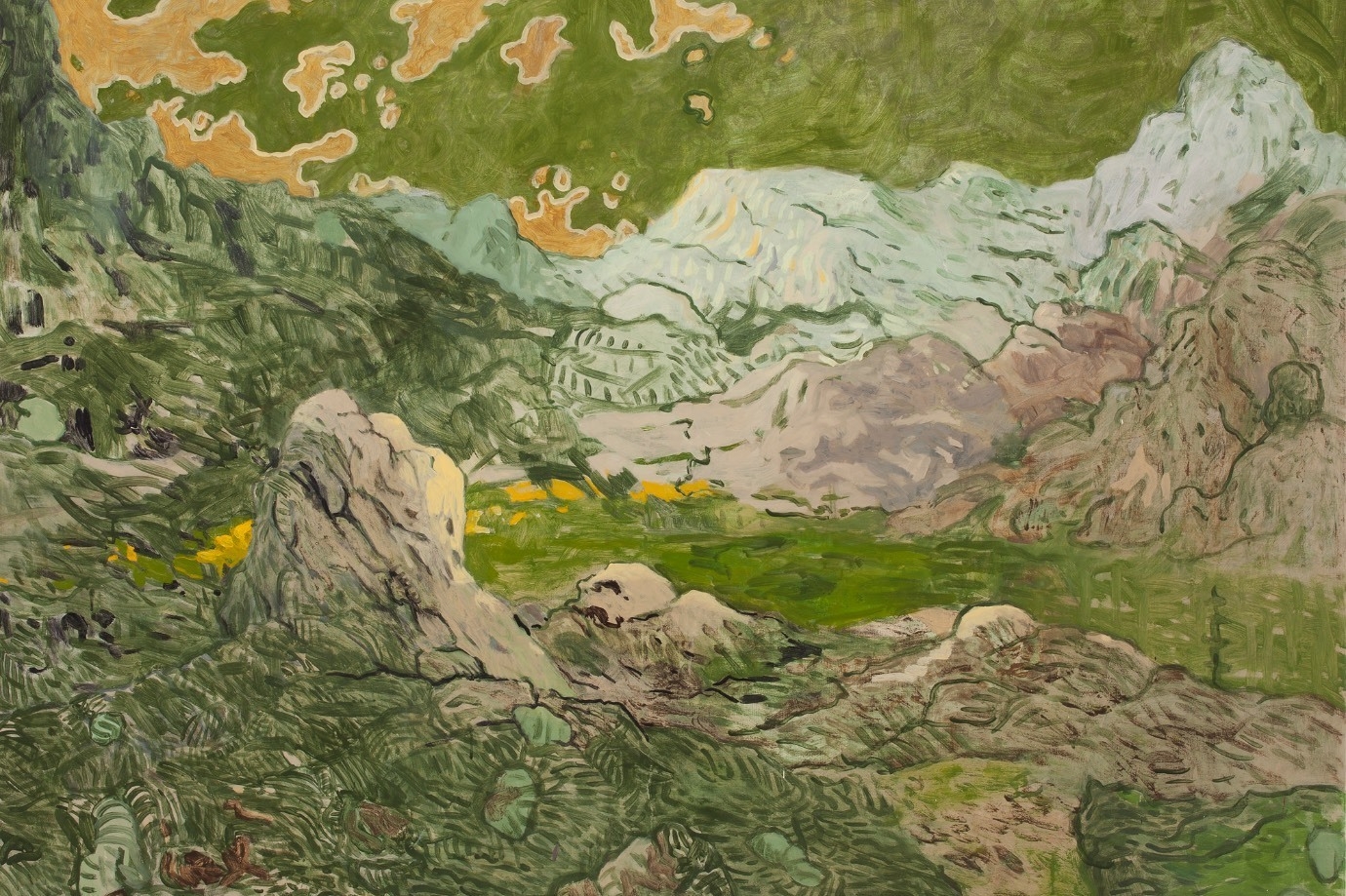

In the new exhibition at Galleri Haaken, Nondal also invokes the vocabulary of fantasy and anti-naturalism. Pictures which we clearly recognize as nature, yet this time imagined in red, volcanic variations of landscape, engage with other coloristic schemes that underscore the authority of fantasy over reality, but also humanity’s equally destructive use of it. A loss of nature, even suggestions of apocalypse, intermingle with a Van Gogh-like vibrancy of line, with a capacity to imbue the canvas and the stuff of painting with the life and miracle of movement.

As a landscape artist, Nondal is both a painter of continuity and fissure; she attentively summons those sublime, elated undercurrents upon which heightened natural experience always depends, but never hesitates to expand, subvert, or transform them—never hesitates to extract them from nature and insert them into that living field of fictions which is painting. Or put differently: the outer, external world never—in the last instance—enjoys precedence over the inner realm. Rather, the image experience itself is fundamentally dependent on the oscillation between the two. Nondal’s paintings become a space of both assurance and incertitude.

In many respects, it is as if Nondal’s catalog has been the object of an eternal summer. Her paintings convey an ever-present desire for cycles of rebirth and revitalization. Man is found wanting; if there are figures in Nondal’s pictures, they survive in perpetual serfdom, always subjected to the sovereignty of their setting. The smallness (and occasionally the greatness) of Man in the face of nature has endured as a trope of landscape imagery from Claude and Poussin through Friedrich, I. C. Dahl, and all the way to Nondal. This is the lyrical legacy of landscape painting to which she could be considered an heir. However, in Nondal’s work nature also opposes and resists the world of which it is inherently a part. Nature questions its own figural architecture and materiality, and thereby reproduces the classical binary between art and life. Still, the paintings proclaim their own internal logic and realism. This directness, this credibility of structure is faintly reminiscent of Magritte’s paradoxical glasnost and straightforwardness—the quiet self-recognition of an artwork that knows and takes its own rules for granted. The histories embedded in such painting are therefore less those of narrative than that of the riddle. Nondal’s visual currency is not that of explanation but rather mystification. Et quid amabo nisi quod aenigma est?, asks a phrase in one of Giorgio de Chirico’s self-portraits from 1911: “and what shall I love if not the enigma?”

Simen K. Nielsen