(4) eset ostukorvis

Hind: €2500

Ruins, knowledge, geography, ecology, memory, landscape, construction and preparation, disappearance. This exhibition, at the Lappeenranta Art Museum, presents artworks that deal with the layers of recording, material circulation, decrepitation, nostalgia and memory.

We constantly predict the future, even though we don’t have any stable ground for predicting what will happen. But in order to hold on to our functional ability, we need to make estimates about how things behave – what is staying put and what is changing.

An image of a situation is not the same as reality, but it is important to be able to form views about the future as well as the past.

The exhibition is based on the joint, artistic research project called In Various Stages of Ruins. Over the course of the years 2017-2022, the curators, together with the artists, considered the relationships between aspects of time and place, as well as the structures and various qualities and processes of ‘ruinification’.

Exhibition presents work from the artists Jussi Kivi, Iona Roisin, Sauli Sirviö, Elina Vainio and Eero Yli-Vakkuri. One aspect of the project leading up to this exhibition were research trips made to Vyborg, to the Karelia area, and through Siberia to Vladivostok. Concepts such as ‘ruin’ and ‘waste’ functioned as instigators of thought for the project, branching out into themes about the formation of knowledge and memory, about the different sorts of perspectives attached to politics, geology, and written history as well as about experiences related to distance, place and the present time. The exhibition at the Lappeenranta Art Museum is partly based on experiences from these research trips, and presents new work specifically created for this exhibition. In addition, and most crucially, the work in this exhibition departs from the research framework and brings forth versatile modes of material attachment and interaction with ‘what is present’.

The curators of the exhibition: Miina Hujala & Arttu Merimaa

Thanks: Katja Kalinainen (The assistant for the ‘In Various Stages of Ruins’ project between the years 2018-2019). Matti Kunttu (graphic design), Jaana Denisova-Laulajainen (Russian translation and production assistance), Anna Ruth (English proofreading).

This research project was conducted with the support of the Kone Foundation for the years 2017-2020. The project was part of the HIAP’s Connecting Points programme which concentrates on Finnish-Russian collaboration, supported by the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture.

MORE ABOUT THE PROJECT / BACKGROUND:

In his book ‘Warped Mourning’ (2013) Alexander Etkind writes about the culture of grieving and memory, within a Russian context. He brings forth the idea that the past does not exist in the present except when created (in the present). Through the examination of literature and cinema he states that the core of cultural remembrance is produced by the interaction between texts and monuments. We need active interplay. He speaks about remembering as connected to time in ‘memory events’, that are re-encounters with the past and create a deviation from established cultural meanings. They change how people not only remember, but also imagine and speak of the past. But the influential power of this is dependent upon their claims to truth; the audience’s belief in the origin of the statements and the importance of this deviation in relation to the identity of the community. When we ask; how is an artist a knowledge producer – at the same time we are asking how the belief in the meaning of various things is created. What does it mean to document and present statements as an active, artistic (creative) action?

Artists Iona Roisin, Elina Vainio and Eero Yli-Vakkuri were invited to form a kind of research group; to make new work related to the subject matter. Roisin examines the role of nostalgia and the position of an outsider through the format of a travelogue-video, and in this way deals with what is possible, or ethical, when approaching different themes. Recorded and captured material from Vyborg, St. Petersburg as well as from the Trans-Siberian train journeys function as the source of material as well as the framework for this travelogue. Vainio also uses a personal approach, especially in considering contradictory sentiments of an experience – with regards to Russia, to the trips made there, and their related implications. A sentence borrowed from Svetlana Alexievich, is divided between Vyborg and Vladivostok in a video work made in 2019. The reliefs made for the exhibition interpret collected and gathered material with private sentiments and thoughts. Water is the material for Yli-Vakkuri’s work where different springs along with various filtration cycles circulate on site as a built-in water treatment plan. The water used in the work was collected from natural springs in Finland as well as from sources found during excursions to the Karelia area.

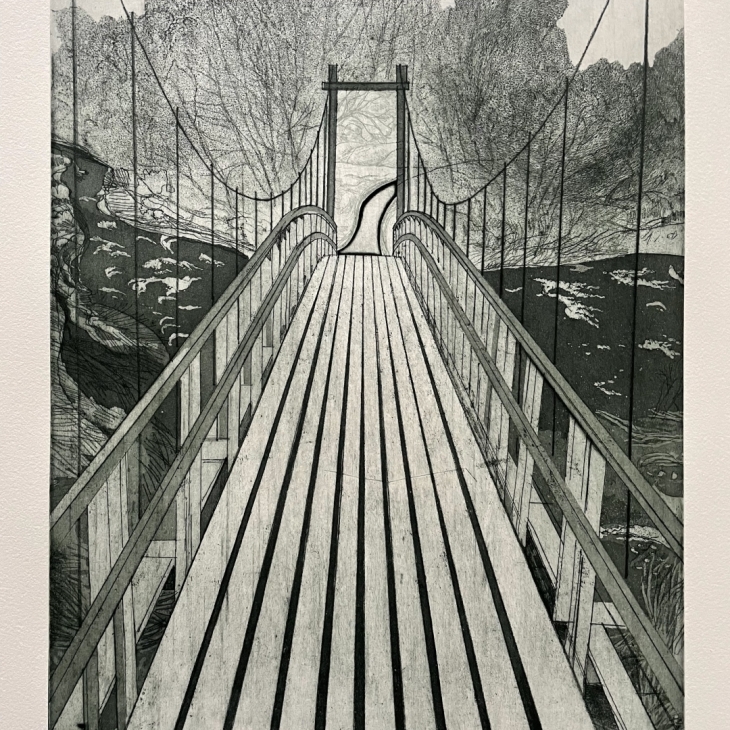

The oeuvre of artist Jussi Kivi, photographer, explorer and adventurer of ruins and remnants, inspired our entire project. In this exhibition are images that record the artist’s encounter with a small American town, using memories along with material from Google street view. How to make a connection to change and movement is an element that is tied into the work of Sauli Sirviö, who has been travelling along many kinds of uncertain and disappearing railways, and bringing forth the dynamics of dismantling infrastructures. We presented Sirviö’s work ‘We need oil to breathe’ (2018) as a part of our mobile exhibition whilst travelling to Vladivostok in 2019. For this exhibition in Lappeenranta, Sirviö made a new series of works where temporal exposure to light, alongside a sort of material excess, play a central role.

We examined realities of the ‘present’; the environment of interaction between people and the possibilities tied to this. Multiple crises of trust – which are not only visible in the atmospheres of politics and information distribution – also aid in maintaining a constant feeling of uncertainty, and make returning to a sort of fictive past easier (looking for nostalgia) – than forming a new vision of the future. In her book ‘Arts on Living on a Damaged Planet’ (2017) Anna Tsing (et al.) brings to light our ‘multiple beings’ in relation to change that the production of science and knowledge have brought forward – not only with regards to our shared existence on the planet, but also in the challenges connected to what we face, as with for instance,climate change and species loss. Tsing and others use the word ‘landscape’ to depict how we are present in our shared reality with climatic, as well as microbial and mineral, realities. Tsing (et al.) also evokes the concept of a ‘ruin’ when she speaks of monsters and ghosts that fill the present; the forms that are left behind, forms that were once meant to be receptive to a certain species’ attributes (like the blossom of a plant that developed the appearance of a certain pollinator’s genitals to attract this pollinator, which has now gone extinct). In order to become aware of these certain types of biological and operational ruins, one needs to adapt the attitude of an explorer, and a museum has always been a sort of collector’s cabinet, where the material relationship to knowledge is continually renewed. But at the same time, the museum is a captor that prevents the decomposition and disintegration of objects. The ongoing loss of nature is acute and difficult to obstruct, many familiar environments and species will disappear, and it might make many of us very melancholic and sad, but it is sincerely crucial to actively form new relationships and to recognise the importance of our existing relationships as well, instead of just documenting this disappearance. Interdependence as well as understanding the versatility of species is important when we seek durable, and possible solutions and worlds, perhaps the title of Tsing’s book presents a way “to live on a damaged planet”.

When thinking of possibilities of how to function in the condition of this ‘damaged planet’, I find it is also about sites and artworks as evidence of various visions of past and future. The role of the museum in relation to truth and the power of proof also provide the possibility to examine the relationship of different forms of control of meaning – especially when doubt is attached to the truth-concept with regards to the authenticity of things. In his book, Etkind recalls: “Medvezhiegorks’s museum director told me that it is easier to open an entire exhibition that deals with political oppression inside the museum than to put a single info sign on to a site of a mass murder.” The ongoing ‘crisis of post-truth’ is part of multiple processes of expansion of communication that accelerate the bringing forth of opinions, but at the same time highlight the need to obtain genuine connections, not only between people, but also in relation to memory and forms of meaning making, in order to deal with what is valuable and what is true. It is relevant to constantly observe how the images of things and events are constructed; images of situations where one has not been physically present, and how to communicate knowledge of being present.

The thematic of this exhibition simultaneously deals with the resonance of memory, knowledge and ruin – within both political and physical spaces – including their distances and layers. This exhibition considers how, and by what means, distance and proximity are built within the constant alteration of the existing world. One cannot help but notice how during the planning of this exhibition there were vast and dramatic changes. How the exhibition that was initially planned for the year 2020, was postponed due to a global pandemic and then, after Russia launched its aggressive attack on Ukraine, the changes which ensued were not only experienced in the practical aspects of the exhibition but also in the thematic – as for instance with the word ‘ruin’ in our project’s title.While Ukraine is currently, in very literal terms, being bombed into ruins, it is not only the past which is being brought into question. Ruins are constantly being made. Condemning the war and supporting Ukrainians – in all possible ways – is of the utmost importance. This also means limiting collaboration with Russians. Over the years we have worked with many Russian artists, and have wanted to bring forth mutual understanding in order to build a future despite the effects of the ever increasingly totalitarian regime. In the reality of war, things are not the same as before. We completely understand that it is not easy for the people in Russia who are against the war, and it is hard to foresee any alleviation, but the forms and routes of interaction have to be recalibrated.

The perception of different distances, along with how they are constructed and maintained has been an integral part of this project and we therefore specifically chose to present this exhibition at the Lappeenranta Art Museum. Lappeenranta is close to the Russian border, and to Vyborg, as well as to the Karelia area where our explorations took place between 2018-2022. We can’t, and we shouldn’t bypass the importance of these locations as integral parts of Finnish history. Remembering is an elemental part of history. The present is not a self-evident totality but one that is in constant formation. The exhibition The Surface Holds Depths participates in acknowledging this processing and formatting of memory.

Text: Miina Hujala

Galerii nimi: Lappeenranta Art Museum

Aadress: Kristiinankatu 8-10, 53900 Lappeenranta, Finland

Lahtiolekuajad: T-P 11:00 - 17:00

Avatud: 04.02.2023 — 21.05.2023

Aadress: Kristiinankatu 8-10, 53900 Lappeenranta, Finland

Lahtiolekuajad: T-P 11:00 - 17:00

Avatud: 04.02.2023 — 21.05.2023