NOBA’s main office is located in Estonia, but The NOBA Young Painter Award is not your first encounter with this country – five years ago, you were regularly tripping between Riga and Tartu, drawing in the bus and finally opening an exhibition here. How did this happen?

Well, I could say my curiosity about Estonia started much earlier. I spent my childhood and teenage summers in the countryside close to the Estonian border. Later I learned that I also have an ancestry line coming from there – my great-grandmother was Estonian. So I developed an interest in Estonia, collecting Estonian books translated to Latvian, watching Estonian films, and my very first study choice was to study in the Philology faculty mainly for three reasons – I loved literature, they had lectures about theatre critique, and they had an Estonian language course. I even got accepted, but in the last moment decided in favour of Culture Academy. Some years later, I met my partner – an Estonian guy – and moved to live with him in Tartu, and now in Tallinn. Most of my active socializing time is spent in Latvia and during my studies, I was travelling there and back every few days, so Tallinn, for me, so far, was mostly a place for rest and quiet work at home.

While living in Tartu I started a small drawing series of the area where I lived. Small size drawings, because I needed something I could easily carry with me in a backpack. We lived in Supilinn (Soup Town) where all the streets are named after vegetables one could use to make soup (and some berries, too). A few houses away were the remains of a building where a famous 19th-century Latvian poet, Eduards Veidenbaums lived during his studies. So it was a very poetic, inspiring area, filled with old wooden houses, gardens, and rooster songs in the morning. A bit later, thanks to the Latvian society Tērbata, I had a chance to exhibit my drawings of Supilinn (and also some of Tallinn and some of Latvia) in the Philology faculty building of Tartu University. It also was a great joy to take part in the Latvian Textile art exhibition in the Noorus gallery.

And some years later Tallinn was added to your journey and another exhibition was opened. How would you compare those three cities – Riga, Tartu, Tallinn?

Yes, Tallinn is where I live now. Part-time, at least. During my studies I often joked that I actually live in the Tallinn-Riga-Tallinn bus.

In a way, it’s a bit hard to compare because Riga is home – everything is familiar and seems easier to reach. In Tallinn, all the distances feel longer, although the city is a bit smaller. One thing that was very frustrating for me in Tallinn in the beginning, and still is sometimes, was the street layout. I was used to the Riga centre, where streets mostly cross at right angles and make up clear blocks so it’s not hard to keep a clear map in your head. In Tallinn, this often got me in situations where walking seemingly straight, I ended up in places I wouldn’t have imagined at all.

I guess it’s somewhat similar to how I see the art scene in these two cities as well. Riga has a very clear structure with predefined paths: first, the studies, then participating in group exhibitions, learning to organize your own, finding people with matching interests and so on. Tallinn is more of a terra incognita for me thus far. I have caught a few glimpses, but COVID was limiting my access to more active participation and I also haven’t yet moved here in terms of my professional career. So Tallinn’s art scene is still something to discover for me.

At first you studied cultural theories at the Latvian Academy of Culture, then continued with textile studies at the Latvian Academy of Arts and ended up in the painting department? Would you have become a different artist if you would not have such a strong theoretical background?

I think studying multiple subjects has given me various tools and perspectives for looking at things.

The textile department trained me well in technical flexibility, creating works using different techniques, learning new tools. And also patience, as why I liked textile was my love of texture as well as works that require patience over a long period of time (weaving or embroidery, for example). Similarly, in painting, I feel much better using an approach that maybe sometimes takes unreasonably long. But I feel that my approach of layering the paint and getting extremely close to every detail also creates a very personal relationship with the painting. So even if I am painting a place I have only visited for a moment, while painting I sort of live there for a while and have a feeling I know the place and its tiny quirks and secrets.

My studies in the Culture Theory department were targeted mainly towards histories (history of literature, art, theatre, music, philosophy, religion, etc.) that offered me different ways how to link various topics and time periods. In a way, I think most of my inspiration in art actually comes from literature and history, and a good working knowledge of history allows me to gain a much deeper understanding of what I’m painting.

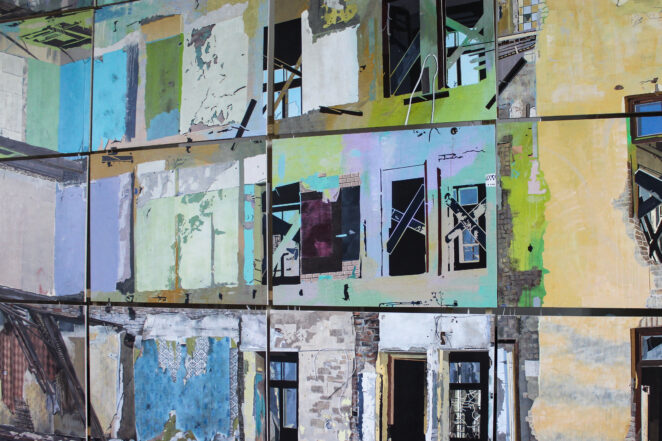

The winning work of NOBA Award Building – 4,8 x 6,4 meters massive painting “34 29” – is a semiotic idea of umwelt (“environment”, “surroundings”) as well as modern knowledge about how human brains process information. It consists of 16-parts painted “impression” of Katoļu street 29 (formerly 34) in Riga and its purpose is to develop a better understanding of what houses mean to people and what it means to lose a home. Why exactly this address, this building?

This house is located a block away from my home in Riga, so I had seen it since childhood and had a chance to follow its life closely. The idea of painting this particular house has been in my mind for several years. And my master’s work seemed a good enough opportunity to try, as I knew I could not squeeze this story into a small painting. I had various ideas about the materials and the execution of the work. After considering everything carefully, I decided to do it as a traditional painting on canvas as it was important for me to use a somewhat traditional approach but on a big scale.

Sometimes I choose a place to paint based on the facts I know about it. But more often, there is some visual inspiration first and I gather the information about the place while I am painting. Sometimes it’s newspapers you can find, sometimes materials in books or archives, sometimes all I have are the stories or rumours I have heard. All these scraps of knowledge create a story for me, a story that I need to be able to develop a feeling about what I am about to paint. It fills the empty spaces and merges them with my imagination. But I rarely include those stories in the description of the work as I believe viewers should be free to create their own stories. I’ve had several occasions where people came to tell me about their old homes, homes of their grandmothers, aunts or brothers. Insisting that they looked exactly like the ones I have painted. So for me, it’s more important to pass on that tiny colourful thread and allow people to remember and recall their own stories, to take a closer look at their own home, instead of looking up the exact address I have painted to compare the realness of the picture.

That’s why most of my paintings are simply called “Walls” and a number.

And those bold bright colours of the walls are hiding so many stories. Some of them I had read in the news – when the inhabitants were suddenly evacuated because there was a danger the house might collapse, some flat owner had just returned from the market with food for his cat, and his main worry was about returning to his pet. Reading old advertisements from the beginning of the 20th century, I discovered a lot of details about the daily lives of its inhabitants – some flat is looking for a nanny, somebody else is selling their furniture and moving, somebody else is carelessly running a food business and is regularly charged by different inspections. During World War II, this part of Riga was a part of the Riga Ghetto and this house was one of those that marked the border of its territory.

I started the painting in the previous autumn, but the bulk of the work happened in spring alongside the war in Ukraine. And suddenly, pictures of buildings like that were overflowing the media and it got very emotionally heavy to look at the work without thinking of that. I didn’t want to completely change my plan for the work, but it was also impossible to paint not thinking about this new reality. A lot of the things now seemed irrelevant. I felt I didn’t want to overwhelm the work with small details so kept the last paintings rougher and more minimalistic, concentrating only on the most important objects and details that shaped the view and gave it depth. It seemed enough.

A lot of your work is related to (old) houses. Do you believe that buildings have souls, too?

I guess I wouldn’t call it a soul, but yes, I think houses have some spiritual essence. For me, it’s closer to Latvian pagan beliefs that everything around us is alive and therefore deserves a respectful attitude, even human-made objects. In an annotation for one of my exhibitions, I wrote a bit humorously that I see houses as semi-live beings, something like mushrooms, not exactly live creatures but not mere objects either.

It’s hard for me to treat a house only as space, as an object consisting of four walls. As the houses include so many stories of those who built them, of those who lived there, of everything that’s happened there. Often houses live longer than the people who build them, they become some sort of an extension for a human’s life, bearing their memory. Also, there is a tradition to give houses names. When Latvians started getting their family names in the nineteenth century, they were often derived from a house name or vice versa. So a house was a very personal “object”, like a family member.

Like in human geography, a place derives its “soul” from meanings assigned to it by humans.

For this winning work, you developed a special painting technique which you have said: „to be suitable for exploring very personal, very visceral topics that are somewhat neglected in contemporary art in favour of complex cultural phenomenon.“ Does this mean you are somehow trying to go back to the roots of painting, too?

Paying attention to the separate details is how the human eye creates a picture. It sees separate elements and their shapes (cracks, outlines, colour), it identifies them and merges them together in the picture. So it also omits some unimportant or unmatching things, and needs only simple marks indicating the depth, for example. The mind imagines and shapes the picture as it should be according to our mind.

Similarly, when we remember things we usually construct a memory image of elements that had caught our eye, that have been important enough for us to remember them. They mark some anchor points in the picture that we recall, and the rest is filled with logical additions – walls, floor, etc. – that might or might not be recalled precisely. As in my works, I am trying to capture the feeling of the place rather than painting an exact portrait, the elements I choose to depict are chosen based on intuition. They are my guesses about what might have been important to those people who lived there, or they are a selection of the marks they have left that became in my mind connected to that particular space.

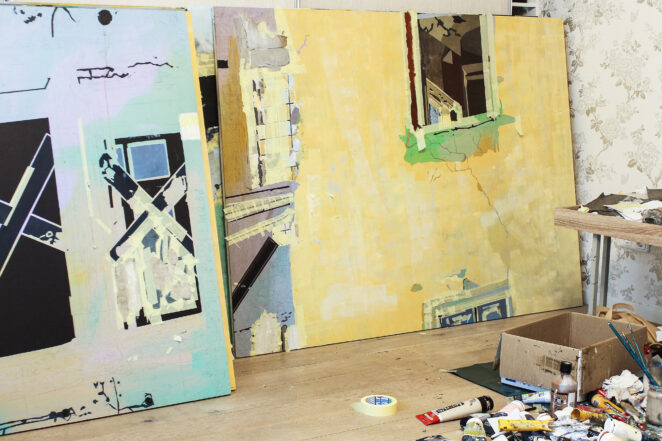

The particular approach I used I developed during my master’s studies: using the brush less and less and replacing it with a roller to apply paint on the walls.

I also often use stencils as well as Soviet paint rollers that were used for applying ornaments. I separate all the details, lights and shades in my painting, encircle each tiny element with paper tape and paint it separately using a paint roller, using a brush only for splashes and some special details that need a more delicate hand-painted touch. The use of tape protects me from getting stuck in unnecessary details, makes shapes simpler, geometrical and allows to concentrate on the essential. This makes a painting look more look like consisting of different cut-out elements which, combined together, create the picture.

I also enjoy the playful process of painting: working on each separate field as a separate thing instead of painting it in relation to others, splashing, dripping, rolling on paint and then discovering how it all blends together. Most of the time, my work consists only of tape patches and is often fully covered with tape. Only after finishing the last areas do I remove the tape fully. I think that playfulness is an important part of creation, and although my approach is otherwise slow, I allow accidents and unplanned elements to shape the work.

Many contemporary artists are expanding the boundaries of painting and art in general. And many critics are calling this phenomenon an „end of art“. Is there any hope left for traditional painting?

Although the borders of different arts have become very vague, somewhat unclear and overlapping, I do not think that it would be the end of art. Artists nowadays have unlimited freedom in their use of traditional approaches, to take them apart, to choose the medium, the tools and the approach best fitting their artistic goal, their idea.

I find joy in playing with layers and textures and trying to capture the feeling of the subject that’s very often hard to put in words but feels fitting for translating it into colour instead. It’s in a human nature to create and to observe.

The story it tells is what makes art interesting for me. Not with words and descriptions but with shapes and colours. Or the lack of them. For me, an artwork’s most important quality is visual, whatever it may be, and the effect it leaves on me; everything else is optional. There are things that painting can do that other medium cannot.

And from what I’ve understood from feedback given to my works, it also works for the people who see them.

Photos of the painting by the author Ingrīda Ivane.