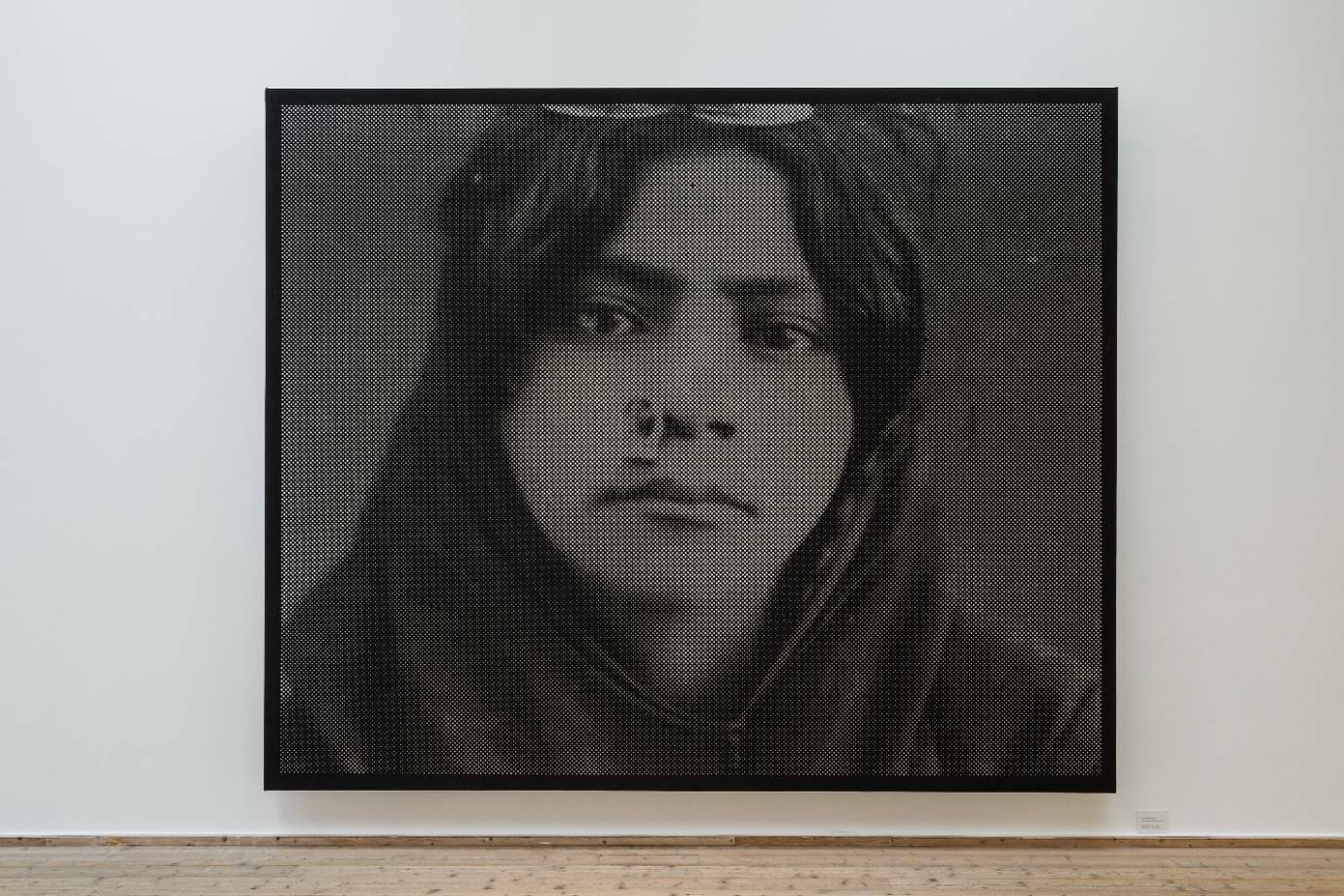

The archival pictures are naturally only a starting point for these artworks. They are cropped to focus on the elements that the artist wishes to concentrate on. The photographic is translated by hand into holes in the canvas using tools developed specially for this work process. The perforation creates a lively visual, kinetic moment giving light and life to the portraits. This becomes clearer when the viewer moves in front of the large-scale works, experiencing how different light conditions cause the pictures to change. Kinetic phenomena are a theme that deeply interests the artist.

Anne-Karin Furunes’ archival images are presented using ways and means that resonate with contemporary art. The scale is often monumental, as if to highlight that the portrayed persons are now being given the focus that was previously denied to them. Their lives were often tragic, due to historical events, but also through personal misfortunes or social exclusion. These portraits have been enlarged to a monumental scale, which conveys a message beyond the individual faces, recalling tragedies of bygone times. The facts about these histories can be found in the information of the different archives that the artist has used.

The portraits show that every person’s human dignity is non-negotiable but has to be continuously reaffirmed. Simultaneously, it seems that at the present time, the main victim is our planet, where the conditions that make life possible for all of us are now under threat. In addition to which, we are witnessing conflicts and wars that bring human tragedy.

An exhibition of Anne-Karin Furunes’ work makes us aware of the familiar truism, that what we see is actually “more than meets the eye”. We understand that the original archival picture has undergone a process that makes it more resonant with contemporary visual ideas and expressive possibilities. Pondering the meanings of these images directs our focus back in time while simultaneously creating a dialogue with the changing overall light passing through the perforated surfaces of these works. This is further enlivened by the onlookers’ movements; the experience of looking is brought into the here and now.

The viewing situation can be analyzed in terms of the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze’s (1925-1995) definition of the time-image in post-war film theories. His philosophy postulates the co-existence of actuality and virtuality. Actuality is not the same as reality, insofar as actuality involves multiple virtual possibilities which the directions, perceptions and thoughts are leading to. According to Deleuze: “Philosophy is the theory of multiplicities. Every multiplicity implies actual elements and virtual elements. There is no actual object. Every actuality surrounds itself with a fog of virtual images.” Analyzing the time-image in cinema, Deleuze writes that “there is not only perception but also a kind of perception of that perception”. Deleuze views “this relationship as one of being in circuit: not only is it an unbroken exchange (…) but its only direction or progression is to lead to further re-interpretations: ‘The actual optical image crystallizes with its own virtual image, on the small internal circuit. This is a crystal image’”. This is defined as the purest crystal image.

The basic element of Anne-Karin Furunes’ art is a photograph, usually a small picture found in an archive. These photographs are transformed by perforation into monumental scale images on canvas with light-permeable surfaces. In a way, these works create their own “tense”, one that invokes the history of the image now presented as a portrait, devoid of any reference of the setting in which the picture was originally taken. They are self-referential in the sense that when looking at the image, we often intuitively know, based on some specific features of the portrayed, that the images are historical. The history of these images with all their actual and virtual interpretation possibilities, becomes part of the present and the viewing situation. The crystalline character of these images creates a particular in-between “tense” that leads the onlooker to ponder one’s own time as well as that of the portrait.

The display of works in this exhibition reflects the fact that the paintings are shown in a setting that bears the hallmarks of another era and the life of another artist. The entire visual situation becomes a kind of total installation, with the various elements mutually influencing the entire scene. Vigeland, his time and tastes are, in a way, the visual hosts of this visit. This is, however, not an uncommon situation, since works of art in private homes mirror this very scene. The viewer is met with temporal and, at times, ambivalent visual references.