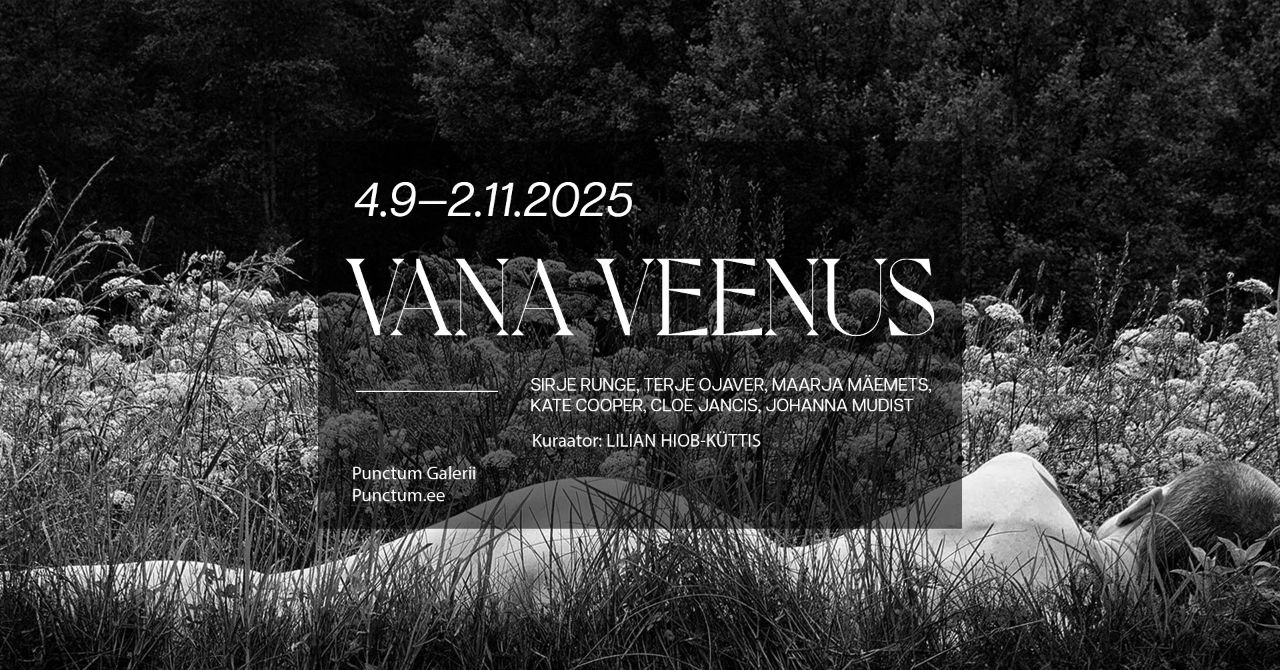

The exhibition opens with Sirje Runge’s photograph “Old Venus”, which portrays an archetypal ideal of a female in mature age. The exhibition focuses on the process of human formation, a journey defined by contradictions, rejections, learning, care, malice, sisterhood, and joy. Artists Sirje Runge, Cloe Jancis, Maarja Mäemets, Johanna Mudist, Kate Cooper, and Terje Ojaver explore aspects of womanhood through what Sara Ahmed calls the feminist killjoy — someone who disrupts the norm simply through her blunt presence.

The exhibition is grounded in N. K. Jemisin’s science fiction trilogy The Broken Earth, in which the main character Essun, a mature woman with seismic powers, tries to survive in a collapsing world while searching for her daughter. Her journey intertwines with those of Damaya and Syenite, younger versions of the protagonist. The unfolding story is filled with violence, control, resistance, and ultimately the shattering of worlds and norms. In Jemisin’s world, as in our own, both the planet Earth and the female characters revolt against systemic oppression.

Kate Cooper’s video work Infection Drivers depicts a computer-generated female figure, her body encased in a tight latex shell. The shell inflates and contracts with the rhythm of breathing, turning the figure into a living mechanism, embodying the stress women carry in a society where ideals of beauty and labor expectations exert invisible yet persistent pressure. The title initially evokes pathogenicity, the body as a carrier of disease, but Cooper inverts this meaning: infection becomes a metaphor for the spread of awareness and deviation from the dominant system. The disintegration happens not in the body itself, but in the structure that produces, shapes, and markets bodies.

The form of Maarja Mäemets’ glass jug references Pippi Longstocking’s red braids. It is a nod to the iconic figure of children’s literature, whom the artist presents as a disruptor of normative order. Pippi defies authority, gender-related expectations, and institutional discipline, being both playful and anarchistic. Mäemets experiments with how everyday forms might be used to undermine social stability and ideological order.

Terje Ojaver’s works Woman with Big Feet and Self-Portrait as a Turtle combine classical form language with personal narrative. Ojaver dislocates the expectations placed on the female body and its role in art and society. Her self-portrait figures do not fit into established social or bodily frameworks. While Woman with Big Feet occupies space with unapologetic force, the turtle-figure moves slowly but determinedly, carrying a shell made of kitchen pots and pans, symbolizing the passive, gendered, and enduring weight of domestic expectations.

Johanna Mudist’s paintings explore family and sisterly relationships as multilayered and evolving bonds, where joy and tension, support and differentiation form a dynamic whole. The paintings reveal the complexity and depth of familial closeness, the reciprocal effects of relationships, and a lasting resilience born from both relentlessness and support.

Cloe Jancis’ work Witch addresses the fears and stigmas surrounding aging through the archetype of the witch. The artist critiques the polished aesthetics of social media and the cult of youth that generates fear and alienation toward aging. The aging body becomes something both familiar and disturbing. This uncanniness, as described by Julia Kristeva and seen in Jancis’ work, disrupts traditional understandings of the female role and visibility in society.

At the heart of the “Old Venus” exhibition is an examination of the female ideal as a historically formed and culturally mediated construct which the artists unpack through critical approaches to science fiction, folklore, literature, and consumer culture. It speaks of bodies that were born, rejoiced, got worn out, carried, remembered — and resisted.