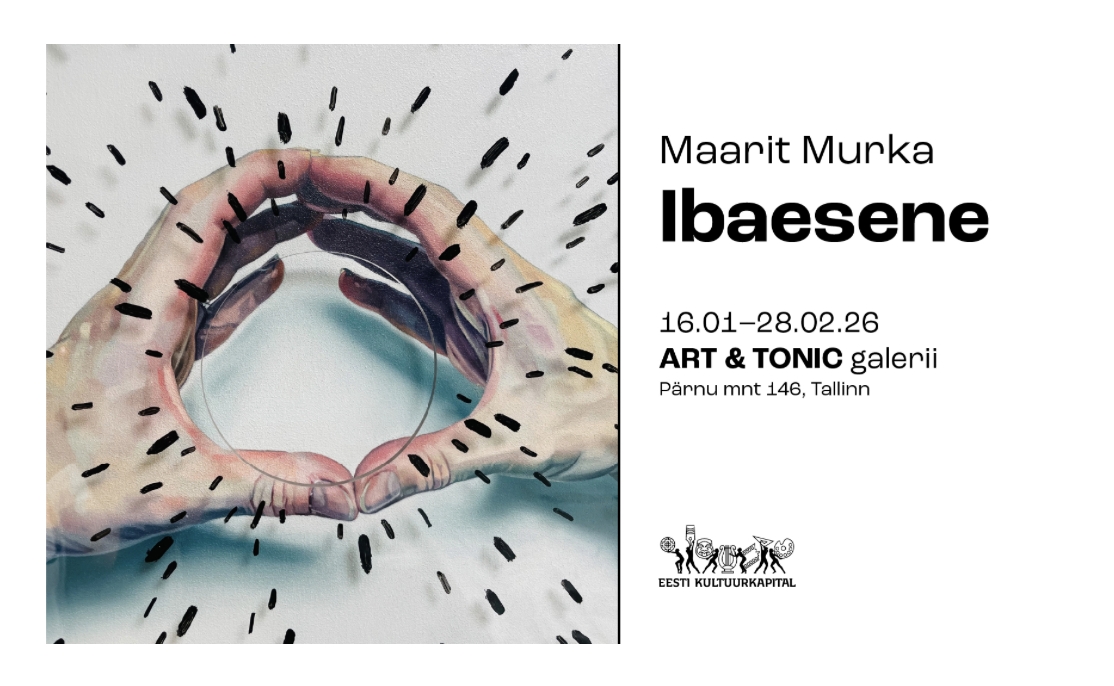

“Ibaesene” is an upside-down “self-help”. Self-help is not a way to fix, but a way to stay functional in a world that puts a strain on the nervous system. In psychology, self-help is called self-regulation, i.e. the ability to notice when internal tension is increasing and the ability to relieve it before it becomes paralyzing.

For artists, the relationship with self-help is much broader and more complicated, as creativity does not come out of nowhere, but requires emotional and mental resources. In art, it is normal to be in doubt, vulnerable, or to live in a constant inner dialogue. The artist is used to observing and expressing her inner world and through creativity to put into form feelings that are difficult for her to express directly. On the other hand, creative work is characterised by a vague goal, constant self-esteem and the connection between the artist’s own identity and the result.

From the outside, it seems that the artist has an easier time with self-help than others. He is used to observing his inner world and giving it shape. Feelings are not alien or forbidden to him, and confusion does not immediately mean failure. The creative process is in many ways similar to therapy, as both require presence, the search for meaning and the shaping of the experience. But this similarity is deceptive, because the need to be an artist can include the temptation to use difficulties against oneself. The desire to turn pain into an identity speaks against them, and personal suffering can become the fuel of creation for an artist, which is difficult to give up. This is where the paradox lies. An artist may have more languages to speak to themselves, but they also have more opportunities to avoid direct care for themselves. Pain can become material and restlessness can become part of identity. The cultural myth of the suffering artist gives a tacit justification to all this.

This exhibition was born with a similar duality. Like countless previous and future ones. No matter where in the world and how experienced or unrecognized by an artist. It can also be called the artist’s nature, which on the one hand includes the revelation of deep personal experiences and, on the other hand, uninterrupted doubts about the necessity of all this.

Maarit Murka describes these poles on her path as follows: “I am constantly working on understanding who I am, why I am and where I am. I’ve tried to move away from it several times, but I’m still being pushed back. So this is my place and path. It’s not easy, but you don’t want to either. Cry if you want, you still go and do it, and in the end you are happy and satisfied, even though the road seems winding and endless during the process. I don’t know where my pictures come from. They just come. Because I have withdrawn from their direct invention over the years. By chance, I come across visuals that I will analyse later. That’s why I have to do the work I have undertaken in one go, because in six months it will be a new time with new visuals, the analysis of which will take us to a completely different place than today.

If I had to sum up what connects these busy situations, it would be the borderline situation of asking for help and trying to find oneself on the edge of it and cope. How does a person position themselves when they have a hard time? For years now, I have been chilling the conviction that I am weaving some strange energy into my works. The same energy drains you while you are doing it, and later, when the work is done, you give everything back again. Like a battery bank. For me, the current jobs are very different from what I have done before. At the moment, I can’t say why. It’s just a different feeling. Although their birth has been inexplicably difficult at times, I cannot use negative undertones and words to describe it – nothing seems to be stopping me. The phrase “what doesn’t kill, makes you stronger” applies to these works, but since there is “kill” in it, that’s why I can’t use it. In addition, I have felt and noticed that someone else is present in these works. I don’t know if this feeling seeps into me from the environment or from the frighteningly much talked about about the impact of artificial intelligence on art, but when I’m having a hard time, I always turn to God or something bigger for some reason. If you think about it, it has been there all along. I remember from the end of high school, where the characters in my essay were the feet of God and other parts of the body. Strange, right?”