Obi (b. 1980, Lagos, Nigeria) created the colorful fourteen medium and large-scale acrylic paintings presented in Exiled during the first stages of the pandemic that coincided with the surge of the Black Lives Matter movement. At the same time, Obi’s paintings are informed by his multicultural upbringing in the Nigerian city of Lagos, where he studied art at the Yaba College of Art and Technology, and the experiences following his move first to Sweden and then to Norway, and the UK. Precisely, the exhibition title reflects all these aspects as it uncovers the different types of emotional, social, cultural, and geographical “exiles” the artist, and perhaps each one of us, has experienced. “We all have been to exile and back,” the artist says.

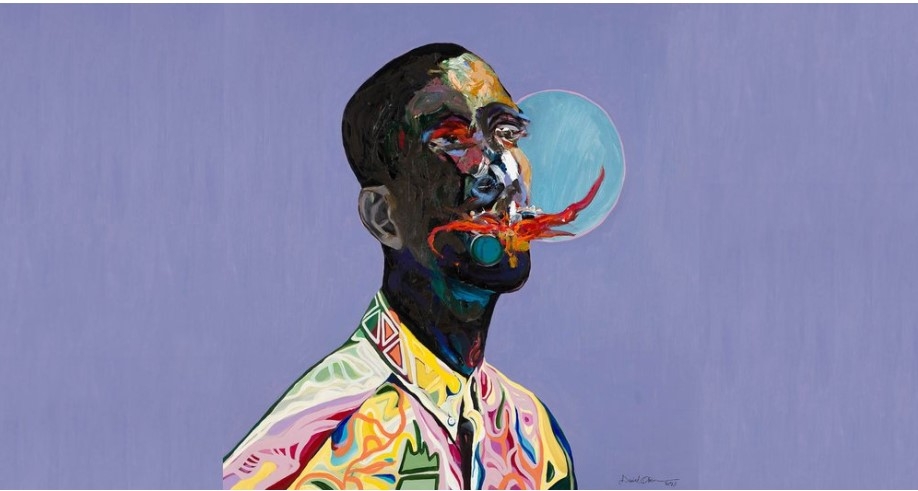

But, who are the subjects of these portraits? Interestingly, David’s portraits synthesize the many social media images, photographs, and daily life characters that inspire the artist’s practice, all of which are connected to the African modern diaspora and to the political and social context in which we live. When creating this series, the artist relied on traditional painting and drawing techniques which he has experimented with for years. Obi’s approach is methodical yet it leaves room for intuition. Each work begins with a sketch and then the artist prepares the canvas with a light wash of one shade of color. Here, the gestural application of thick overlapping layers of color begins and is centered mainly on the character’s faces whose rich textures contrast with the much more delicate brushstrokes applied to other sections of the canvas.

Without a doubt, Obi’s distinctive distorted depiction of the human face threads this portrait series together as it materializes trauma or what happens when we are beyond ourselves. Particularly, in works like Split or Lockdown Buzz, the blue and red thick traces placed on or around the abstract-looking faces of the depicted subjects convey the many worries, emotions, and thoughts that are surpassing them. At the same time, the absence of features allows us, the viewers, to see ourselves in these mysterious individuals. In the artist’s words: “By effacing their identity… I want the viewer to see themselves in the piece as if looking at the mirror.”

Next to its expressive power, the distorted nature of Obi’s faces also speaks to the legacy of European modern and contemporary artists that altered human proportion and which the artist admires. For instance, the work Red Cap Bishop connects us to Picasso’s cubist faces, while other paintings, like The Reader, make us think of Munch’s emotional paintings, and most of them bring to mind the work of Francis Bacon. More so, David also looks for inspiration in the work of seminal African painters, like Nigerians Ben Enwonwu and Uche Okeke, that paved the way for the birth of African Contemporary Art.

Alongside these multicultural influences, David is part of a generation of young Black artists with African roots, such as Lionel Smith or Amoako Boafo, who use portrait painting as a means to reinterpret African visual culture and identity. These aspects have been present in David’s past works through the portrayal of African icons like Nelson Mandela and are also seen in some of the works in this exhibition, through the recurrent use of vibrant colors, mainly yellow and orange, and motifs used in Nigerian art. However, in works like Tommy Boy and Purple Dream, the subtle references to David’s background alternate with the presence of global fashion brand logos on the subject’s clothing speaking to how aspirational brands define the identity of their bearer regardless of their nationality.

Notably, the portraits in this series also have a narrative component activated through the presence of a myriad of symbolically charged objects that refer to the health, migratory and financial crisis. This is seen, for example, in the painting Pandemic News, where the headline of a newspaper placed on the floor connects us to the first stages of the pandemic when the death toll was alarming and we were faced with fear and uncertainty. More so, some of the portraits in this series, like the painting Trapped which includes the phrase “No human is illegal in stolen land” on a boy’s t-shirt, reflect on the ongoing migratory crisis affecting the US and elsewhere. In this way, through this series, Obi makes a subtle yet poignant political and social commentary.

Overall, while connected to the modern African diaspora, the works included in Exiled have a universal nature that goes well beyond a particular race or nationality. They are a testament to how nowadays cultures and regions are connected and to how artists negotiate and interpret the endless influences and referents they have at hand. For Obi, the most important thing is to communicate the intricate layers of human emotion and he does so with efficacy taking us on a journey from figuration to abstraction, and back.