“It would seem that all this is self-evident and does not pose a particular problem, especially in this age of monitors, but it is essentially a metaphysical question. How can an artist depict a three-dimensional world on a plane? Geometric space systems, mathematical theories of perspectives are needed, and all kinds of them: common to all – objects that decrease as they move away, inverse, axonometric, etc. In the 18th century, parallel to the Camera Obscura, the principle of Trompe-l’oeil still life painting appeared. Approaching classicism, the Age of Enlightenment tried to squeeze the whole world into a clear three-dimensional cube space. It seems that the linear perspective of lines converging to one point has finally taken hold. But the oases of axonometry and reverse perspective hidden in realistic still lifes and urban landscapes,” says A. Aliukas.

According to the author, the formulation of the representation of space as an existential question in Lithuanian culture is marked by 1785-1786. The painter Pranciškus Smuglevičius, who lived in Vilnius, and his sepia-painted views of the city of Vilnius. When creating them, he probably used the Camera Obscura, the predecessor of the analog camera, when in a completely darkened room, the light penetrating through a small hole projects an inverted image, which helped artists to accurately transfer objects of complex configuration into paintings.

“Camera Obscura” was a manifestation of the “progress” of those times – a symbol of the use of scientific achievements in the practice of art, the pursuit of true “objectivity”, an experiment in a certain democracy, when it seemed that the new machine could perform the function of an artist, and anyone who could master a machine could be an artist . But Camera Obscura has another, deeper meaning. It reminds us that there is no creativity without the environment visible to the artist,” says A. Aliukas.

“Whatever “new worlds” he depicts, the creator leans on the visible-touch environment, lives in the world of geometry – the “proportions and volumes of the earth”. The artist himself is the Camera Obscura – a creature that contains and recreates the world, a kind of alchemical retort in which all that we call “creativity” condenses. It contains images and experiences of the past and present, so any artist’s retrospective exhibition is a kind of Camera Obscura,” explains the author.

The two-level indoor space of the GODÒ gallery also responds to the principles of Camera Obscura. In the dungeons (basement rooms) are concentrated drawings and works of the past, a kind of origins of the author. The spiral staircase – as if the eye of the Camera Obscura (lat. oculus) moves and transforms the world of the past into the present, rests on the “City Sky”.

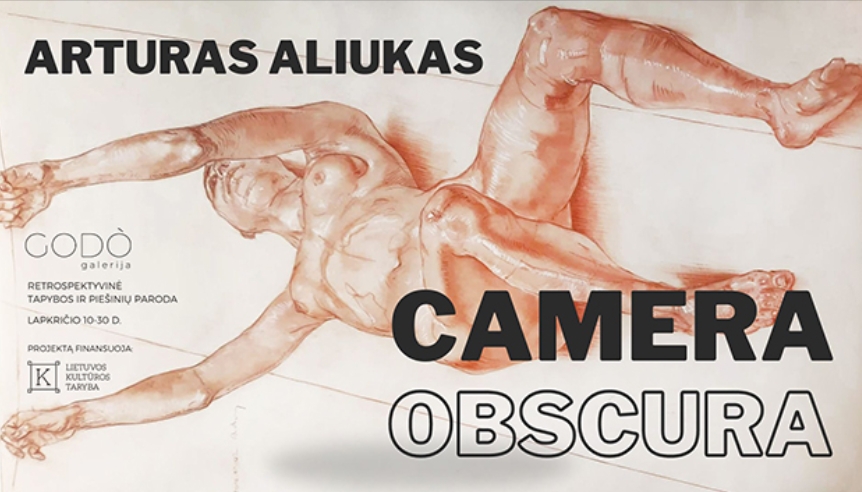

The exhibition in the “GODÒ gallery” becomes the artist’s self-portrait – the artist, remembering P. Smuglevičius, sees himself and the city he lives in and wants to understand.

“I think the subject of Camera Obscura is interesting because of its inexhaustible angles of vision; when examining them, the seemingly uncomplicated theme of perspective and space becomes layers of unusual plots, the viewer’s imagination and metaphysical questions”, says the author of the exhibition, A. Aliukas.