Pardon-me not, 2023

Installed in the former Museum of the Soviet Revolution (currently National Gallery of Art), can be linked to themes of institutional critique, whose development coincided with the development of post-structuralist philosophy, feminism, gender studies and post-colonial theory [1].

The critical practice of Dada and conceptual art emerged as a reaction to the socio-political context, together with a desire to re-evaluate art’s position and role in institutions. The contemporary scholar of institutional critique, Jens Kastner, argues that institutional critique should not only be understood as a movement within the field of art, but also that it is difficult to imagine it without social movements outside the art field [2].

Institutional critique is loyal to the vision of the autonomous institution. In Corneille Castoriadis’s L’Institution imaginaire de la société / The Imaginary Institution of Society (1975), the idea of governance – rational, institutional control – is contrasted with self-management – autonomous individuals and the functioning of society. Where power is based on mechanisms of fear and intimidation, autonomy and authentic politics do not work because the participants are not empowered to consciously and courageously build a common institution. In the world of Castoriadis’ autonomous society, we are each an institution. This is how Denisas Kolomyckis behaves – not only in this work, he is consistent in his daily activities.

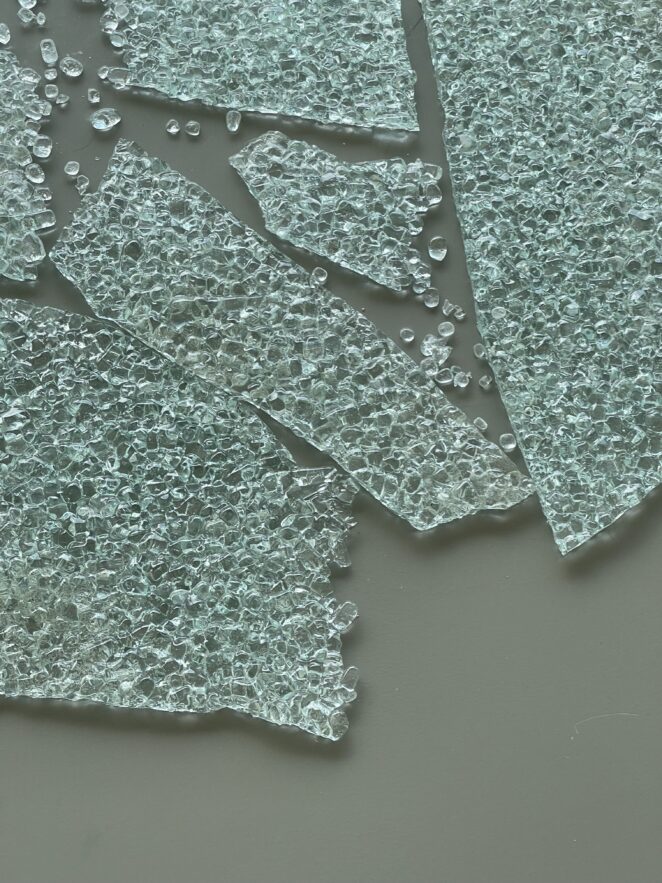

Denisas’ “Pardon-me not” could be described as a study at a museum window. It works through an artistic interpretation of the movement and protest of glass matter – the shards of a posh German Street antique shop window, lying on the gallery floor, peer through the gallery’s sophisticated window. Although we didn’t see the shatter itself, we can imagine it – the unified, representational, edgeless plane of the shop window, crumbling into a community of glass shards, has transformed from a homogeneous mass into autonomous glass parts. Without this intervention, many glass planes would remain invisible. Denisas takes his game of reconstruction further – he continues the polemic by taking the next step of combining the individual shards into an alloy institute, thus making them organised again (in addition to the shattering, they have undergone the 850 degrees Celsius therapy). The surfaces of the alloy resemble the scars of a battle against heat, some more melted, others less so, no longer conforming to the canon of an orderly and rational, elite governing body (Žižek was right, what has been named cannot fail to leave a trace. Interestingly, coincidentally coinciding with Denisas Kolomyckis work, the National Gallery of Art is hosting an exhibition titled Disrupting It Becomes Tangible. Infrastructures and solidarities behind the post-Soviet condition”). “Institutional virginity is tainted”, as anthropologist Mary Douglas would say. Can autonomous parts become invisible again? Perhaps – with more heat?

The installation invites the museum itself to look out of its window. The relationship with the antique shop suits the museum, because the museum itself is an antique shop, actively transforming itself into its own exhibit. The self-referential vector has already become a recognisable axis of the museum’s self-referentiality, and the evidence is right there – on the floor, next to the work, we can see one of the museum’s narrative plaques about itself. By offering the tables, the museum is consolidating the status of the artwork, but also contributing to the recuperation of the social aspect of the work. This action only reinforces the museum references in the work and offers counterfactual scenarios of the museum’s already broken windows. In a formal sense, we can observe an aesthetic jigsaw puzzle of rough alloy on the floor (which is also an ingredient of the enjoyment of the work’s sublimated texture), while the anomalies in the composition prevent the viewer from being struck by the banality of the unlocked work.

This game of smashing and gluing could go on and on – the initial institutionalisation is not the final stop – only a puzzle that repeatedly denies the discovered rhythm can satisfy the inexhaustible thirst for new knowledge. Boundaries cannot disappear, they can only shift, deconstructing the subject of research down to the grains of sand that caught the current coming through the broken window, disintegrating to a form never to be seen again. The institution that frees itself from institutionalisation has essentially two paths, either to remain self-referential, exhibiting in its own showcases, or to engage in a self-deconstructive game, trusting in the hold of autonomous art. But for now, the shards melting behind the closed, thoroughly cleaned museum window, safely surrounded by dusty, free museum stands, are lucky – otherwise they would be wandering autonomously in the city’s dumps. Apart from the combativeness and aesthetics discussed, the work is strangely melancholic. Not just because it doesn’t apologise (“Pardon-me not”), but for the reason it doesn’t apologise. Denisas Kolomyckis “Pardon-me not” is poignant in its “The dragon is dead! Long live the dragon!” in its inevitability.

In sum, Denisas Kolomyckis has created an elegant, visual metaphor for a violent act, in which the broken glass symbolises the aestheticised and institutionalised lives of the victims. As a reflection of the consequences of actions and the fractures that arise from societal tensions or personal choices, the motif of the broken window encourages the audience to reflect on complex social dynamics and the transformative power of acknowledging and addressing these fractures to seek understanding and change. The installation of the work at the National Gallery of Art raises questions about the role of the art institute in society and its ability to relate to difficult issues in the here and now, while also providing a statement of resistance to the institutions that perpetuate violence. The title phrase “Pardon-me not” is an unconventional construction that can be interpreted in many different ways, depending on the context and intended meaning. One interpretation is that of a refusal to ask for forgiveness when one holds firm to one’s convictions in defiance of societal expectations or norms. “Pardon-me-not is also a refusal to accept forgiveness; it does not provide a polite absolution until a new understanding is reached. Finally, we may recall James Q. Wilson and George Kelling’s theory of broken windows, which states that no matter how rich or poor a neighbourhood is, one broken window will soon lead to more broken windows. Or, perhaps more optimistically, one could refer to the Terminator’s iconic hand-breaking window. And top it off with “I’ll be back”, Denisas Kolomyckis “Pardon-me not” statement. Denisas Kolomyckis installation “Pardon-me not”, his final master’s thesis at the Vilnius Academy of Arts, is on view until 16 June. The exhibition is on view at the National Gallery of Art (Konstitucijos pr. 22, Vilnius). — [1] Takac, B., Reading Into The Institutional Critique, Then And Now, Widewalls, 2019, https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/institutional-critique-history-context, accessed 16 February 2021. [2] Kastner, J., Artistic Internationalism and Institutional Critique, in Raunig, G., and Ray, G., Art and Contemporary Critical Practice: Reinventing Institutional Critique, MayFlyBooks, London, 2009, pp. 43-50. — Explict from the annotation written by dr. Eglė Grėbliauskaitė