Tell us the story of how you started your journey in the art world – when you decided you will become an artist, which were the first exhibitions you visited, the first artists that impressed you?

I don’t remember my way exactly. I have been studying art since I was 6 years old, starting with an art school in my hometown, later – art high school in Riga and then The Art Academy of Latvia. I also studied at a music school, but while still studying, I realized there was a complete lack of talent.

My father was good at drawing. When he sent letters from the army to my mother, he always drew some kind of a small caricature. I assume some skills were inherited.

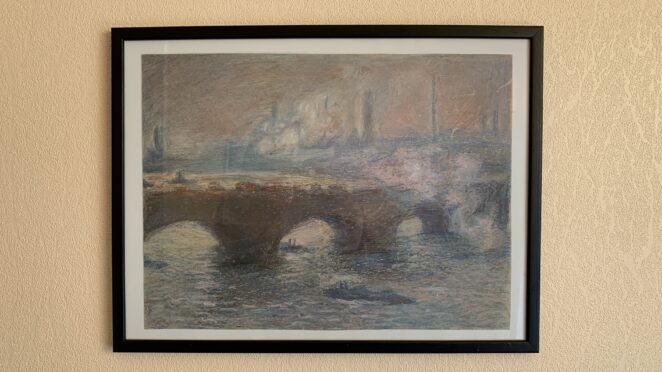

I am not sure if it was the first artist, but I remember being influenced by Monet, already at the children’s art school. The school assignment is still preserved – a reproduction with pastels – Waterloo Bridge, Gray Day. From today’s perspective, it seems like an interesting choice for a 13 year old. But it is natural when you get to know the classics – of course they inspire you, that’s why they are considered giants of the art world. A little later came Dali and Bosch, the architect – Luis Barragan.

The first time I went outside of Latvia specifically for an art event, was to Pärnu, Estonia – a performance exhibition. At first it seemed that it will be a live performance event, but by the time we arrived, we came to a conclusion that it was a retrospective photo exhibition. We got to know all the artists and spent a wonderful time in Pärnu for a few more days. I was a big fan of performance art then, later came my great love – Arte Povera and land arts, which is still current today.

You studied painting at the Art Academy of Latvia. By now, you have tried to distance yourself from painting’s most traditional forms. You have said that you think that painting can be created by using many different materials and you are interested in experimenting with various materials, substances, and chemicals. This sounds like a proper laboratory – describe to us some of your most fascinating experiments!

The first time that I tried to paint non-still life outside of school frames was in Georgia, at an artist’s residence. There were many different pigments in the form of powders. I started trying them out by mixing them in oil. Among them was also a powder of unknown origin with a metallic smell, which I used like the others, later I noticed that it reacted in a peculiar way with the solvent and the other pigments, forming some kind of a top layer of crystals. So far I have not found what kind of powder it was. In Georgia, I also used gasoline instead of turpentine. Later, in Latvia, I tried to paint with oil paints and bleach as well as rust and clay.

The paintings I created in Georgia are still there. They are large format, some of them are my favourite creations of mine. For now I cannot afford to transport them to Latvia and create an exhibition but hopefully one day. The last time I was there, I visited my paintings and noticed that they had changed. All this mixture with gasoline, the unknown powder, continues to react and change. So, that’s quite fascinating for me.

Many contemporary artists are expanding the boundaries of painting and art in general. And many critics are calling this phenomenon as a „end of art“. What is your opinion?

If we talk about Hegel’s theory, I understand it more as not “as the end of art”, but inevitable changes in our relationship with art, in our perception, in our analytical approach, which no longer allows us to look at art only through sacred or sensual perception. But this is a comparison with the time when it was created within the court or the church.

And otherwise, it seems to me that the boundaries are inevitably expanding – as it happens in all spheres. For example, artificial intelligence which is becoming so much in demand now. I don’t know where its limits are in production.

But what happens to each of us and what we achieve when we are alone with our art does not need to be conceptualised or theoreticized. This, for example, is still sacred and sensual to me.

We seem to be at a critical point in the understanding of values, reproduction of art, artists and art markets. Contemporary art is the result of theory and feeds theory. Maybe actually we are at a crisis of criticism, a crisis of art institutions. Art and artists are going to die if, for participating in a triennale you pay for work, installation, transportation and receive one copy of catalog… Either way, the end = the beginning.

But for critics – It’s also not too motivating to create art in a time that is defined as „the end of art“, I would say.

The war in Ukraine has changed your attitude – you reassessed your interests, priorities and opportunities in art as a form of communication. At the moment you are focusing on memorial art and responsibly socially active art. At least in Estonia there is a debate going on whether to remove the old soviet time monuments and memorials. How is the situation in Latvia?

According to the law “On the prohibition of exhibiting objects glorifying the Soviet and Nazi regimes and their dismantling in the territory of the Republic of Latvia” until November 15th, Latvian municipalities were instructed to dismantle 69 of the 162 monuments surveyed by the National Heritage Board. The law will not apply to monuments, memorial signs, plaques and places, architectural or artistic creations located in the burial places of soldiers who died in the war, as well as in the memorial places of victims of Soviet or Nazi terror.

Before dismantling each object, it was necessary to find out the time of its creation, the purpose of its installation and its ideological message, the impact on the public environment, as well as the artistic value, architectural quality of its original details or fragments, or its cultural-historical or educational significance.

It also happens in Lithuania and as I see in Estonia also.

Extensive thoughts about what is happening are going on and going on in me. Both from the point of view of commemorative art, artistic heritage, historical evidence… Anyway, in my opinion, the urban environment should be cleared of nerve knots, let it rest and then think about its further improvement. There will be new monuments and they are needed, but they must be clearly much more aesthetic that don’t degrade the environment. But primary monuments are a step in the process of healing collective trauma, its concrete legacy, intended to speak of what people related to them had emerged from, how they wanted to be remembered, and what they hoped for. Not the militarily ones nor the ones glorifying great aggressive powers .

Your winning work of NOBA Award – memorial GARAGE 119 – is also related to the war in Ukraine as it prevented you from attending your grandfather’s funeral in Luhansk and you decided to create a memorial to say goodbye to him. He, typically to this generation, had lived under many regimes. How have his experiences and memories affected you as a person and as an artist?

His experiences affected me as a person in a way of acknowledging circumstances in which my ancestors lived – directed me to the desire to find out norms, atmosphere. I am not a child of Soviet times and I was not born and haven’t lived in Ukraine, so we have different experiences, but my everyday environment also consists of Soviet leftovers, which I was somehow trained not to see or, more precisely, do not pay attention to. But now I do – as I see the tentacles of this opressive – machinery stretching out again.

This installation consists of many materials – rust, fabric, video and audio – which also have a symbolic meaning. Which kind of symbolic meaning exactly?

So, corroding and rusting of iron is called rusting. Rust is brittle and its formation weakens the metal and causes accelerated deterioration of iron products. Rust does not protect the metal from further corrosion either.

In this work in particular, it has several meanings. First of all, rust is one of the biggest enemies for car owners. This is an unwanted process. It also indicates a state when the process of rusting has begun, for example, metaphorically speaking, the process of rusting in society – rust in each person’s mind. This is relevant both during the Soviet period discussed in the work, and nowadays when it comes to the Russian society and government.

At the same time, it matters in terms of time. Because time is one of the necessary elements for rust to occur. Over time, new layers of rust appear, equivalent to memories and experiences.

You graduated in 2022 with the Vilhelms Purvitis Excellence Award, 2020 you were nominated for XII Young Painter Prize and 2018 for SEB Painting Prize. And now – the Grand Prix of NOBA Award. How would you compare all those prizes? Which of them has required the most work and which has the most emotional meaning for you?

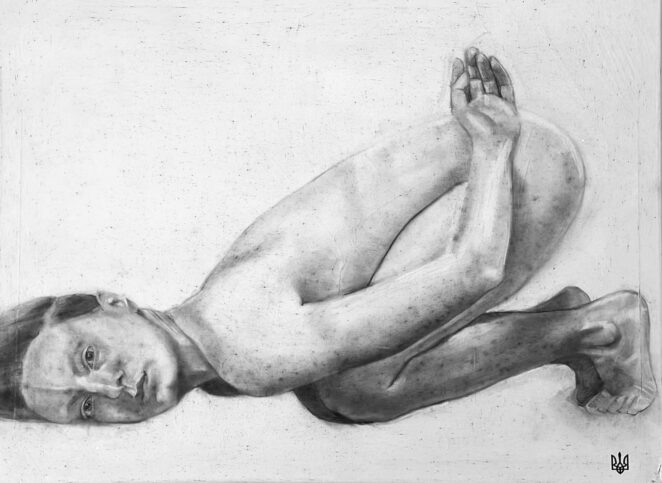

Each of these awards and competitions have been different. The SEB Painting Prize was my first group exhibition where I exhibited my paintings, before that there were only a couple of installations. It was a big event for me. Because the road to painting was different, even scary.

The Young Painter Prize, on the other hand, was peculiar in the circumstances in which it took place. Before the opening of the exhibition, covid restrictions became stricter and the exhibition had to be closed to the audience. As a result, both the opening and the exhibition took place without visitors. The paintings were physically located in the gallery, they had to be brought there, but they could not be viewed. A very weird experience in my opinion.

Of course, the biggest work required was the creation of the Garage, it is a very extensive work in all dimensions, it required a lot of effort, starting with finding the venue, because it was basically the basis of everything. If there was no space valid according to the parameters, the final result would not be the same. All the time, there were some obstacles on the way, which constantly made it difficult to create the already quite complicated work itself. I am happy and grateful that the invested work and energy paid off and that the work was appreciated. What I would like in the context of NOBA is the re-exhibition of this work as part of this award because the Garage requires a physical experience which was missing in this competition, as it was online. Therefore, without this physical experience, you cannot really have a full-fledged emotional experience.