A small shop in the suburbs of Pärnu. A barbershop in Puhja. An accounting office in Maardu. Estonia advertises itself to the world as a place where founding a company only takes a moment. Great. What about ending business activities? In the 1990s, many were glad to exploit the newly liberalised opportunities for entrepreneurship and haven’t stopped doing business ever since, although continuing their entrepreneurial activities hasn’t been their heart’s desire for a long time.

Small businesses, or more accurately micro-businesses, form about 95% of Estonian companies. Most of them have only a couple of employees, often only one: the owner. 28% of all entrepreneurs are women. Great. Of these women, 72% are solo entrepreneurs. How many of them think about quitting each and every day?

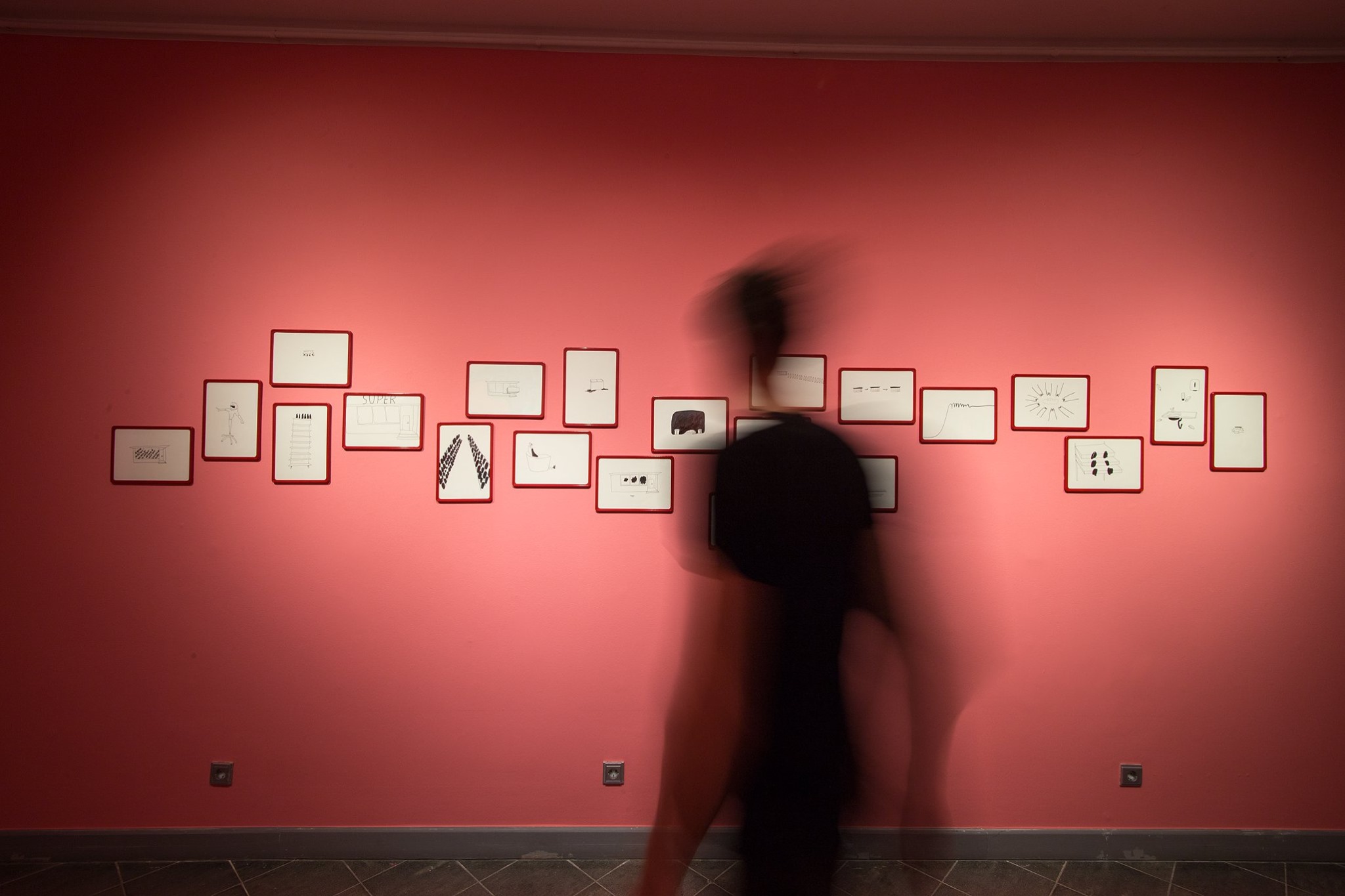

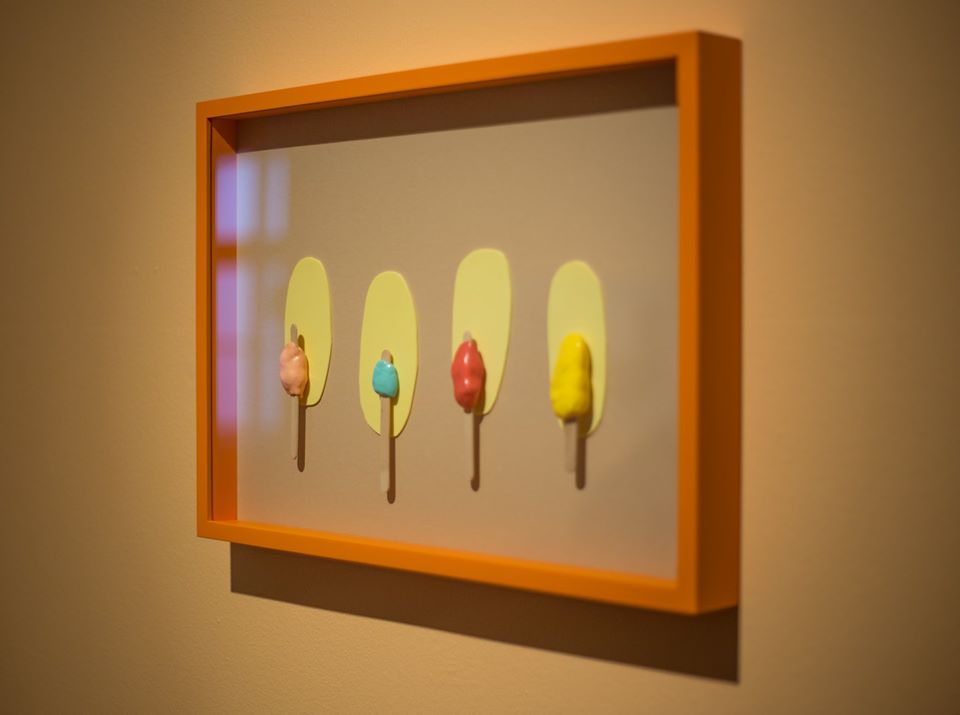

Estonian artist Flo Kasearu works with many topical issues in her work, such as freedom, public and private space, the economic crisis, the role of women and opportunities in society. She prefers to reflect real life and real experience as a starting point in her artwork. “Endangered species” is no exception either – this time her exhibition talked about the village shop led by her mother for 24 years. While there is a lot of discussion and encouragement in media about starting a business and startups, ending the business received far less attention. The closing of the village shop was the inspiration of the artist’s latest exhibition, and its is spiced up with humour and irony, intrinsics of Kasearu’s work.

The market says when you wake up.

The market says when you go to sleep.

The market says whether you celebrate St John’s Day.

The market says when your birthday is.

The market makes you hate Christmas.

Interview with the small business owner Margo Orupõld, whose shop is the protagonist of the exhibition. /Extract from the exhibition’s booklet/

How was your small grocery store born?

I didn’t have a childhood dream of running a shop. It was just chance, as happens in life. I have been living near this store most of my life and shopped there as a child. The store stood empty for many years when the Soviet era ended and state-owned commerce ceased. Nobody wanted it. It seemed tempting to create a place of employment for myself next to my home. I bought the store and that’s how I became a store keeper. Since I had a higher education in economics, that lowered my worries and decreased the risk. Everything went really well, but over time the process became routine, and routine kills.

What sort of help did you get from the local government, state funds, private supporters or your family throughout the years? What was the thing that you missed the most?

The local and state governments are not interested in entrepreneurs who can manage on their own. You seemingly don’t exist. The state becomes interested if you are on a trip and you forget to send in some report. The bank repeatedly offered me a loan and I repeatedly refused. Back then there were no training programmes that would tell you how to make things easier on yourself. My family has been associated with all stages of having the shop. My mother and daughter have worked behind the counter and my husband has repaired broken pipes or windows at night or has shovelled snow and thrown sand on slippery roads.

Why did you decide to close the shop in January 2019?

I had been running it for over twenty years but for about two years it had become routine. There was no excitement and it didn’t offer anything for my development. I had new side projects that were more interesting. The routine stuff takes up a lot of of your time: you can delegate some of it, but you are still responsible. And then you ask yourself, “do I want this?” Owning a small shop is no real challenge. What miracles can you introduce or develop? I wouldn’t introduce a robot to say hello: the clients don’t need it.

The customer wants to interact with a human being or wants to get his produce quickly and go home. Where is my personal development in all of this process? I even started selecting a different route to go home, since I didn’t want to pass by my own business. In such a situation, something has to change. The decision-making is the hard part. They aren’t just snap decisions. What will become of the employees? Will I become a person who makes others’ lives more miserable? Today, the biggest problems are with the staff. The staff always have so many rights and no obligations. They are like children: all children know their rights but they don’t know their responsibilities. They don’t want to actually work, and only do so when they have to. All of the cashiers would try working somewhere else but understood that the situation was no better. And they didn’t dare tell me that they had been trying out other jobs. A regular employee only thinks about their own salary but not about where the money for it comes from. I don’t want to say that an employee should think about the business earning a profit every day but the world view of people should be wider in this day and age. And there is a certain attitude towards me as a businessman.

In addition to the disappearance of small shops, the exhibition also points out the vulnerable position that women have in society. What distinct features have you noticed when it comes to female entrepreneurship?

I recognised the role of women as entrepreneurs later. I was a solo entrepreneur. I didn’t notice any difference even when I had to nurse my parents. It was actually my husband who stayed at home and took care of my mother. I didn’t have to stop being an entrepreneur because of that. It’s mostly female entrepreneurs who participate in training sessions.

Women are less likely to take risks. Sometimes they have two university degrees and still they don’t dare to even start. For women, closing a business means failure, but for men, it might be just another challenge.

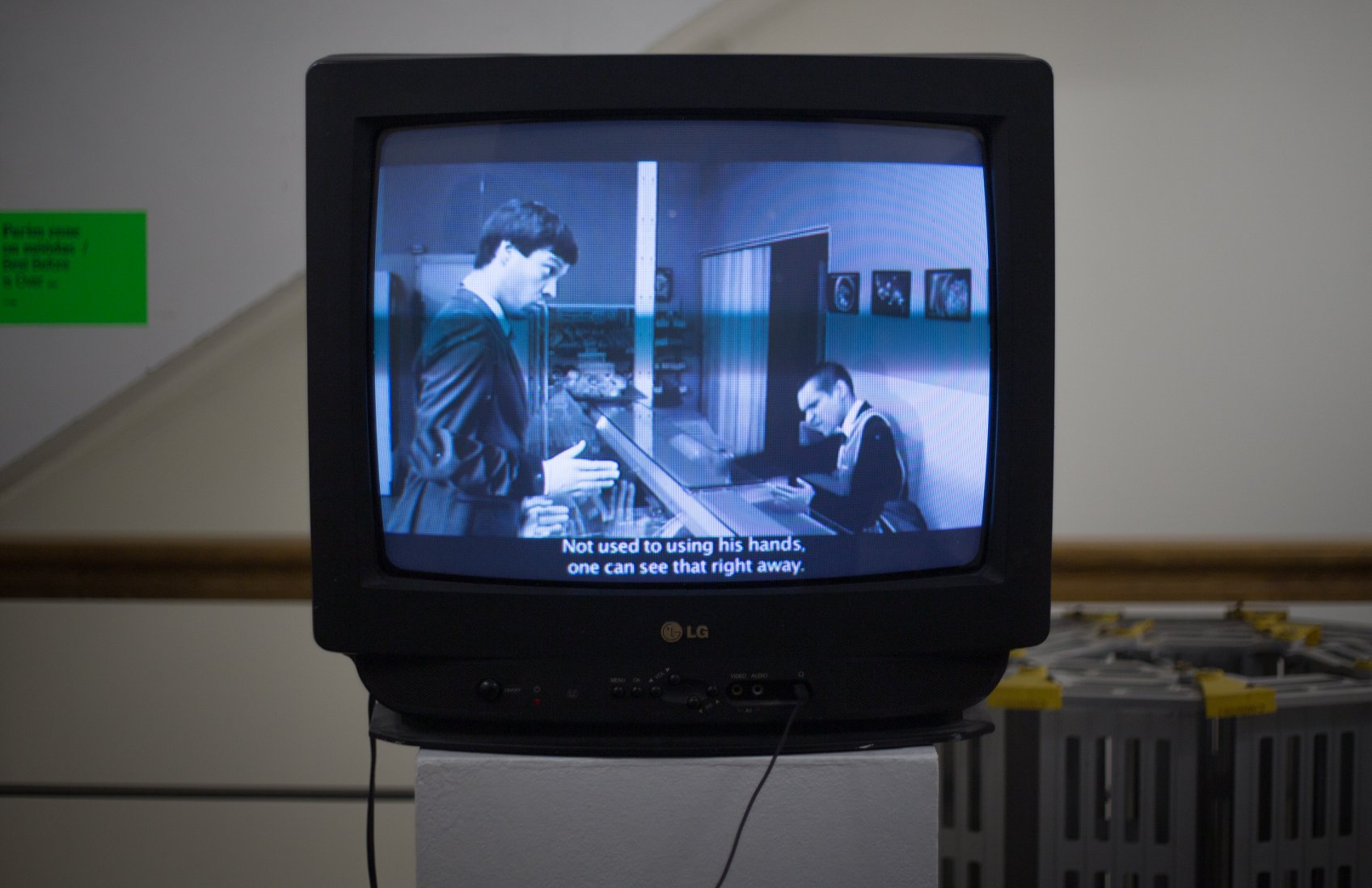

Enjoy the videotour with English subtitles

Virtual tour of the exhibition

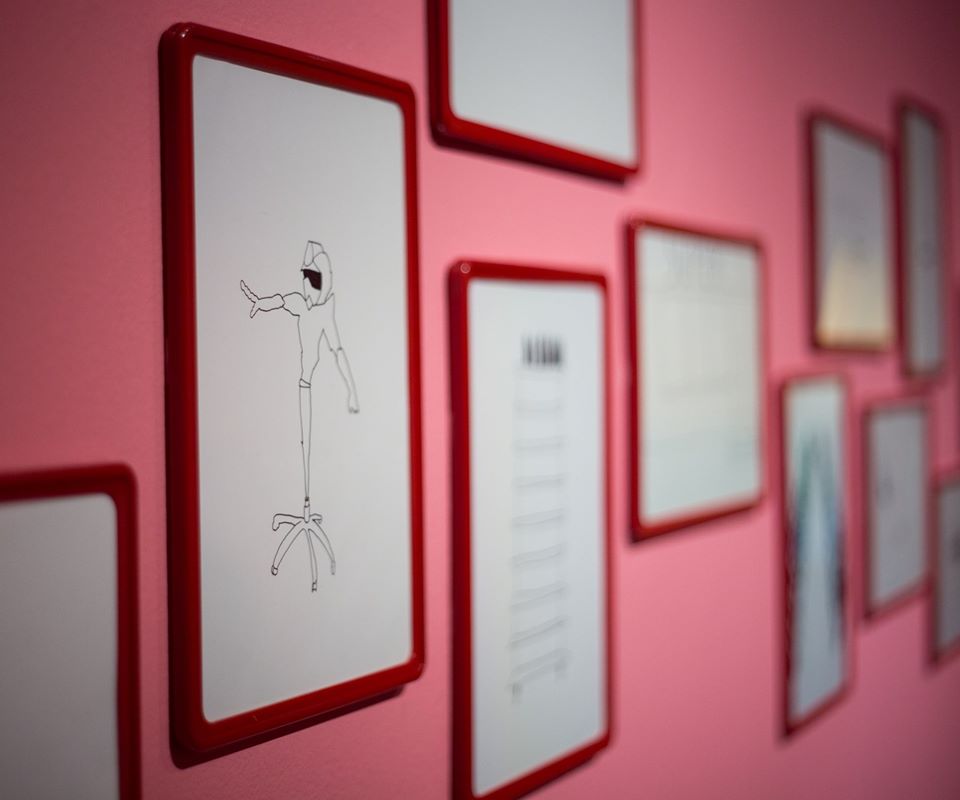

Exhibition views by Taavi Piibemann

Curator: Marika Vaarik

Graphic design: Mirjam Reili

Textual dramatist: Laur Kaunissaare

Assistant and consultant: Hanna-Liis Kont