How has the Swedish art context changed in the past 25 years?

It has been changing quite a lot. Index started in the nineties, and then there was the Nordic dream and an exportation of art from the Nordic countries.

There was a political plan for exporting, not just Sweden, but all the Nordic countries together. From 2000 to now, it’s been a process of trying to understand. This moment of extreme visibility was connected to the market as well. There’s another type of situation now. Some international connections were made at one level, but then it was not necessarily affecting the local context. So, from 2000 to 2010 it’s more of reflection. Now I can see that artists are getting more connected to research. The process of working is more connected to ideas and they need to think more about what they are doing.

From 2010 to now, it’s been a combination of local and international art all the time. At the same time if you look at Sweden, it’s extremely delocalized. What happens in Stockholm happens in Stockholm, what happens in Gothenburg happens in Gothenburg, and so on, but there are not that many links in between these cities, links are with outside, international field from city to city.

Why is that?

I don’t know, probably tradition, a way of doing things, the idea of each city, Stockholm is also kind of snobbish.

You said that in the nineties there was an effort to communicate outside and the commercial art world was also influencing the general art field.

It was a time of the nineties where the channels were clear – to be in an international context meant to buy an advertisement in Artforum.

So, when it appeared, it also was saying something, it showed a status that you could pay the money to do an announcement, you could play this game. Now it’s much more complex. You can do this, but it is not saying that you can play in an international context. It’s much more complex with social media, too. With the fact that every institution is a sender of information and information is divided, we need some people or platforms to select the data. The whole structure is different.

Do you feel it’s more difficult for an artist and art institutions in general now?

I think so, and also because there it’s much more than before, there are more institutions. Index has been here for 25 years, Mint has been here for three years, Konsthall C for 15 years. There are more institutions and more artists.

Everybody is saying that’s an issue, the funding gets lower, because there are too many players in the institutional field, also there are a lot more artists. Should we regulate it somehow?

We have to find ways to work with that. From our position, what we do here institutionally is quite cheap. The percentage of money that goes to artist production is quite big in comparison to bigger institutions, big museums have probably 5-10% that goes to production of exhibitions, here it’s much more. But it’s true that times are difficult and we don’t know what’s going to happen with everything. It’s affecting a lot and it’s also connected with politics.

What are the most important political decisions or laws in Sweden that have influenced the art world in general?

In Sweden, there’s a quite stable system, and it’s an old system, so artists are getting funded directly and it’s beautiful. Many artists are getting paid for being artists every year and it’s a stable system. Artists in Sweden can get quite easily like 12,000 euros per year to just be an artist.

It is very Swedish and if you look at the structure of the government, you will find a specific department dealing with artists -that’s extremely beautiful as it’s straight for the artists- but not for the art system. You can get support as an artist for travelling abroad and production of artworks, being an assistant for another artist or getting a salary for being an artist. It helps the system, of course, because artists are quite fine economically or some of them. And as they already have some economic support, they can spend time producing afterwards. It changes the system. If you have this support to the artist, then you have a not relaxed but safe environment.

But it also means that the idea of art is traditionally based on the artist and the state museums. If you look at the public sector – what happens to art institutions is not clear. Galleries work by themselves because it’s a commercial system. Politics will indeed affect more and more. We can see it now here, right-wing politics want to cancel all contemporary art, they want classic art instead. SD had it written down as part of their program for the elections. It is very easy to break down the system, rebuild it is another thing.

Are you afraid of what is going to happen?

Yeah, of course, because all of us, all the institutions are extremely fragile and we all work a lot to make it possible. It’s not that there’s a margin of gap, we are always spending all the money every year, so let’s see. At the same time, it’s true that, for example, Index has been surviving for 25 years.

Politics is getting more and more polarised, it’s scarier now than ever before because it’s affecting the structure of the state more than before. And it happens everywhere, if you look at the US with the Trump administration, it’s really easy to destroy a cultural context but to rebuild it is another story. We come from two years of Corona and a year of war, too.

To observe the art context in a country shows a lot about the situation of this country, because you can see if there is a desire for knowledge, for experimentation, if there’s a political freedom or not, you can see it in art. Because art is going in and out from the system and from society. It’s a mirror and it’s reality, it’s a reflection and the object.

It’s a key thing really, because it means that you have this case study that is supposedly not important but shows the quality of the country on a democratic level as well. For me, countries that are supporting dance and art, have a good value on society because they understand that it’s fine to have some things that are probably not that easy to understand. It means that they respect their societies because they understand that their citizens are smart people.

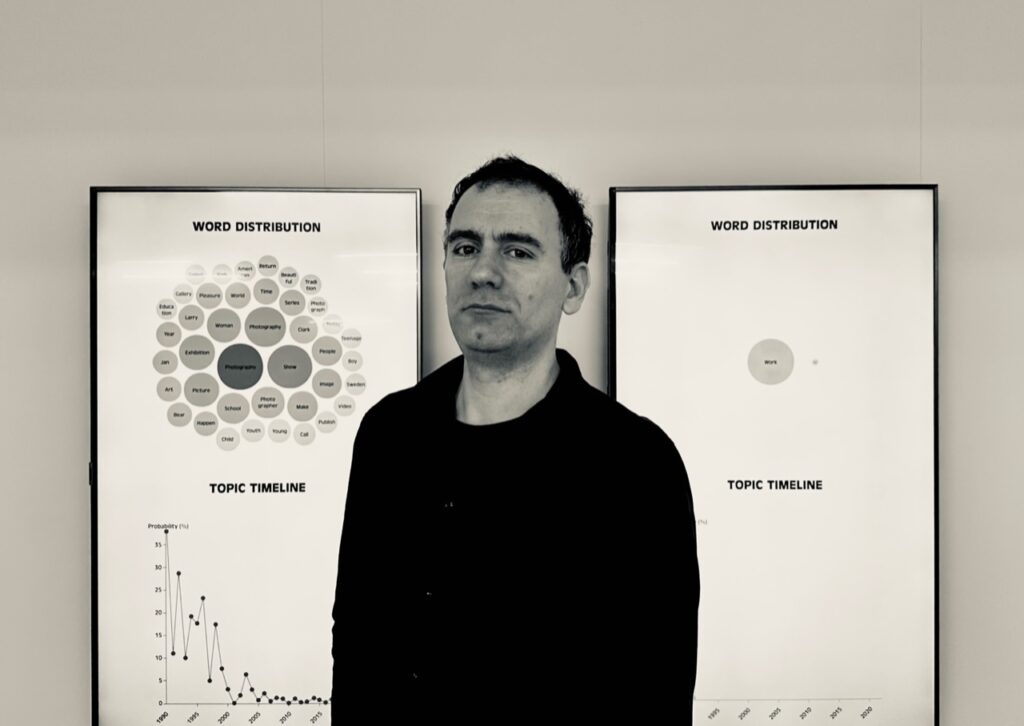

Current exhibition celebrating the anniversary showcase the research of the change of the language over the past 25 years. So, what are the main changes?

For example, it’s interesting to see how the concept of time is quite new in this institution at least. Before it was space and now it’s time. If we look at history, at some point, we go from the question of identity to the question of performativity, it’s all connected with time. And then theoretically, something happens at this point, but it’s a focus of course. Revisiting the archive is connected with time and changing of things.

You can see it in all of the institutions: it’s not just about space and exhibitions, it’s about programming. And at this moment events are essential, to invite people, you can’t do just a show, there’s some general desire for meetings. If you communicate only in an exhibition as an item, then you have three months with nothing to say. So that’s something connected with social networks, it’s associated with a multiplicity of platforms to talk about art or culture.

So, like the time it means performativity and action, which are more relevant from 2000 to now. At the same time, the image was more interesting before, during the nineties. The word man as such disappeared at some point and now it’s really low. We talk about people in another way now in terms of language, but then it was assumed that man included everyone. Basic, but it makes sense to look back and analyse what has happened with us, how we have been writing, all of us. How it has been changing how we talk.

For example, publications has been very important for Index all the time because we work a lot with book production, with the idea of a book. In research, the written word has gone up and down in some periods. This is very interesting, it’s not a subjective approach, it’s software, automatic reading of things.

Contemporary art deals a lot with contextualising and analysing, is this analytical side of the artwork already more important than the artwork itself?

No, the artwork and the artist are the starting point for everything and then the other partner in this dance is visitors. So, what we do is to be part of a dance between artists and visitors.

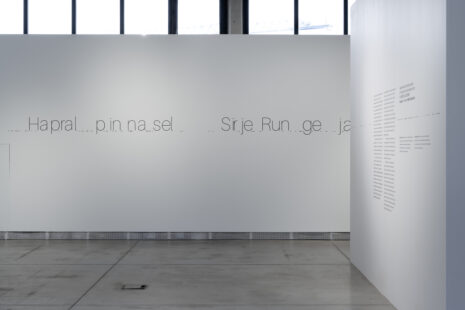

The analytical part is also something that we need to do to understand what we are doing. And this exhibition is to make it more transparent. This A4 text next to the artwork is politics, it has a type of language, and it has a kind of power relationship with you.

As we work with groups of teenagers, for example, we check text reactions with them. Not to make it easier but to make it more complex to understand who the receiver is. With text production, it is one sided, you give something out, and there’s no possibility for a dialogue, it’s telling you how to think about it.

Here we work at the exhibition premises, so it means that people talk with us all the time, and we talk with visitors and they can see us here. Easier or more complex? It’s like you know the machine, and sometimes it’s not easy to see the machine because it’s not clear to see the structures. So, here when you visit Index, you visit one exhibition and also one institution. While in many museums, the office spaces are far from the exhibition.

In your press release, there is a sentence “after 25 years doing, testing and experimenting”. Can you still apply the word “experimental” to Index?

This is what defines Index, this idea of experimenting, like testing and trying to see if there is more behind the boundaries. What’s really interesting is to see that with experimenting, we feel safe because there is a history behind us. It’s essential to have a connection with the archive and its history. 18 years ago we did something similar and we can connect it now. And both cases are experimental. It’s interesting to see that the same questions arise all the time.

What is the budget for Index?

It’s a low budget, we work with 3 million SEK (approx. 270 000 EUR) per year and with this budget we do four to five exhibitions, study programs, research, podcasts and we try to do publications as well.

How are you funded?

We start from zero every year, we have to apply every year and it’s very difficult. But we have been surviving for 25 years, it is possible because it’s a small machine.

Funding comes from the ministry of culture, the city of Stockholm, EU support, the region of Stockholm, and then international project money. So, international networking is one of the key elements.

The next exhibition, for example, is a co-production between Index and Secession in Vienna and Kindl in Berlin. Together we have produced a new film from by US artist Jordan Strafer, last weekend there was the opening at the Secession with this exhibition that is coming also here. And we work together with Publics in Helsinki and Praxis in Oslo, for example.

You mentioned that the small size of Index has been useful, so it’s a decision not to grow in terms of a format?

It’s a nice format. It’s the whole ecosystem of this kind of institution. You have the big museums, they are stable and safe, and then you have the small ones like us that have to be super flexible, take risks. So, we can take risks that big museum can’t.

How do you feel the world situation has influenced the art world in general?

As we are small, we could work during Corona, and we were producing exhibitions and opening exhibitions and inviting visitors here, but it was a time to rethink as well about how to work, what to do, how to communicate, how to think. I think that we will see results in a couple of years.

The tempo is really high all the time. We go really fast, all of us, and suddenly, there was a break in the system, it was possible to rethink. This is why time is important as well as a concept because we can reformulate the ways of working.

You mentioned that Index is like a small secret, but generally, do you feel that the art world is somehow isolated?

It’s isolated, but at the same time, if we can get a page in a newspaper, we have a lot of visibility if the newspapers are writing about what we do. It’s a double thing all the time. Index is a secret. Indeed, it’s still an effort to come here. But if you are coming to Stockholm as an international art visitor, there’s no problem, we are a super central institution.

If you have to name five institutions in Stockholm, Index is probably one of them, but who else? Are there similar kinds of institutions like Index in Stockholm??

People usually know about Index because for our history, then Moderna Museet.

We collaborate with Mint, for example, they are pretty new, but we have a pleasant conversation with them. Tensta Konsthall, also Konsthall C has the same kind of format. What’s beautiful about Stockholm, we have these small size institutions that are powerful on a conceptual level.

There were ones that I was mentioning before but also Marabouparken Konsthall, Accelerator, Färgfabriken. So there’s plenty of institutions on the same level, like between the public institution and the independent ones. With some of them we share ideas, some are more connected to the artist’s run. All of us are very small and most of us 95% public funded.

Then there are public and private institutions like Bonniers Konsthall, magazine III. If you look at the city of Stockhom, that is not that big; you have like 20 art institutions.

How many visitors does Index have?

After Corona it is challenging to talk about numbers because there was a decline and I think we are now at 12,000 visitors. But then again, for example, in the case of teenagers, we work with ten of them. We don’t do visits for schools having 50,000 students here for 30 minutes, because we think that it’s not a good idea as art demands more time. You need time and you need to talk about it. If you have ten youngsters and you speak with them for one year, then it happens. Then you can spread information, and they can talk with friends.

How many employees does the Index have?

Four, including two in the core team at 100%, it’s really small. But it means that everyone knows everything. That’s a lot of work to make all the educational programs and podcasts. It means that there is an engaged team here. Also, we have many artists that we work with. The level of production is just insane. But this is what we do, and this is what we love to do. But then of course, like every person has his or her abilities. We invite external people to work with us. It’s important to understand that the Index universe is bigger than its centre, we have a lot of people around. That makes it possible, without them it would not work.

Index has an advisory board?

We have our regular board and then a group of teenagers that get paid to be our teen board. For us, it’s gratifying because it means we are in direct contact with future practitioners. We really have to listen to them, they can be really critical while learning. And this is a good thing.

That’s an interesting concept, how does it work exactly?

I present the year program twice, first to the board and then to the teen board to see reactions on both sides. Index Teen Advisory Board also knows our budget, they know the ways we are working and thinking, It’s a new situation for them. It’s a job for them, it’s paid although almost symbolically, but it’s paid. They can apply for this position and we have 7-10 teens per year. We already have continuity, it has been working for seven years, it’s a long time already. And for us, it’s now part of our institution’s core. So, it’s not just one program; it’s not profit based. It’s something that we do all the time.

How is the Index exhibition planned?

We decided together; Index has some precise functions, it’s the place where many Swedish artists perform their first institutional show. It’s a place of international desire. So, it means that we bring international artists here as well and it’s a place where we reconsider history.

For a period of time, Index looked at East Europe, and conceptual practices from the seventies. Now we have been observing history through feminism and queer theory. And it means bringing another type of artists that have been forgotten, for example, like for the last five years, we have been programming solo shows only with women artists. It’s a balance thing with history.

And again, after 25 years, we still need to balance gender and at the same time, we have non-gender artists. It’s super interesting how to have this perspective in programming.

But the decisions are made in-house. We sit in the exhibition space, so we are very close to the public, the visitors and artists, and we listen to them, it’s pretty flexible. Then, of course, we have several types of programming, we have exhibitions, and we have a lot of other activities also.

How do you keep updated with the art world?

Well, this is super difficult now. Of course, the newspapers and magazines are still there, but we also follow other institutions and their programs around the whole world, it can be from MoMA in New York to independent art space Simian in Copenhagen etc. There you can see the artworks and meet the artists. Of course, the significant events are still important and will forever be. Venice Biennale is crucial, Documenta, Manifesta are very important.

I’m constantly talking with curators from other institutions to share information about artists. Last weekend I was in Vienna, also visiting artists and galleries, and talking about art with colleagues.

And recommendations for the viewers?

Art gives you a lot when you are on it. After the artistic experience, you will look at things in an exciting way. It’s also an activation, how to look at everything.